All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, October 6, 2016.

vegetarian in a leather jacket

art, travel, culture

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, October 6, 2016.

![Venus of Willendorf (Willendorf Figurine) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [original image]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8290-768x1024.jpg)

![Venus of Willendorf (Willendorf Figurine) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [high contrast version]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8290-1-768x1024.jpg)

![Venus of Galgenberg (Stratzing Figure) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [original image]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8292-768x1024.jpg)

![Venus of Galgenberg (Stratzing Figure) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [high contrast version]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8292-1-768x1024.jpg)

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, October 6, 2016.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, October 6, 2016.

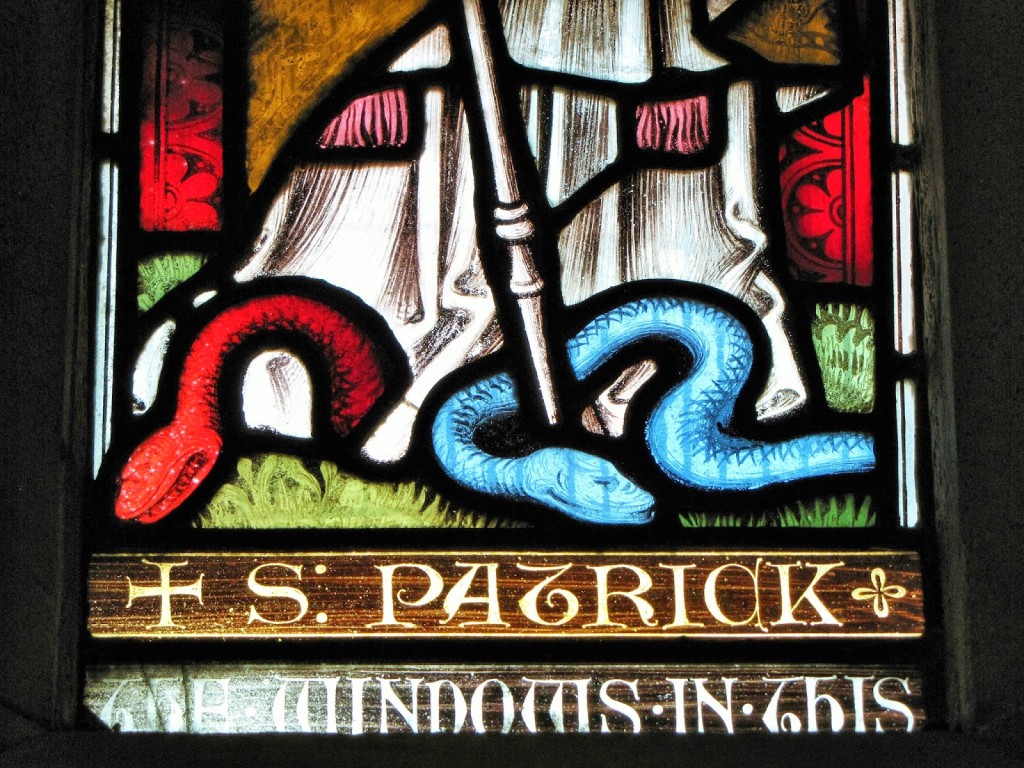

The National Museum of Ireland was originally founded in 1877 when, under the Dublin Science and Art Museum Act, the government purchased the growing collections of Leinster House (now the seat of parliament) and the Natural History Museum. Today, the NMI is divided into four branches: Archaeology, Natural History, Decorative Arts and History, and Country Life. Each branch occupies a separate building, and only the first three are in Dublin. Both the museums of Archaeology and Natural History are located within easy walking distance of Trinity College, the National Gallery, and each other, making it possible to visit all four on the same day.

Archaeology [photography not permitted in most galleries]

The Archaeology branch of the National Museum contains a variety of artifacts—including objects from Rome, Cyprus, and Egypt—although the heart of its collection comes from Ireland itself. The museum’s extensive holdings span prehistory to the Middle Ages. In addition to several of the world’s finest examples of Celtic art, they include one of Europe’s largest collections of prehistoric goldwork and Iron Age bog bodies.

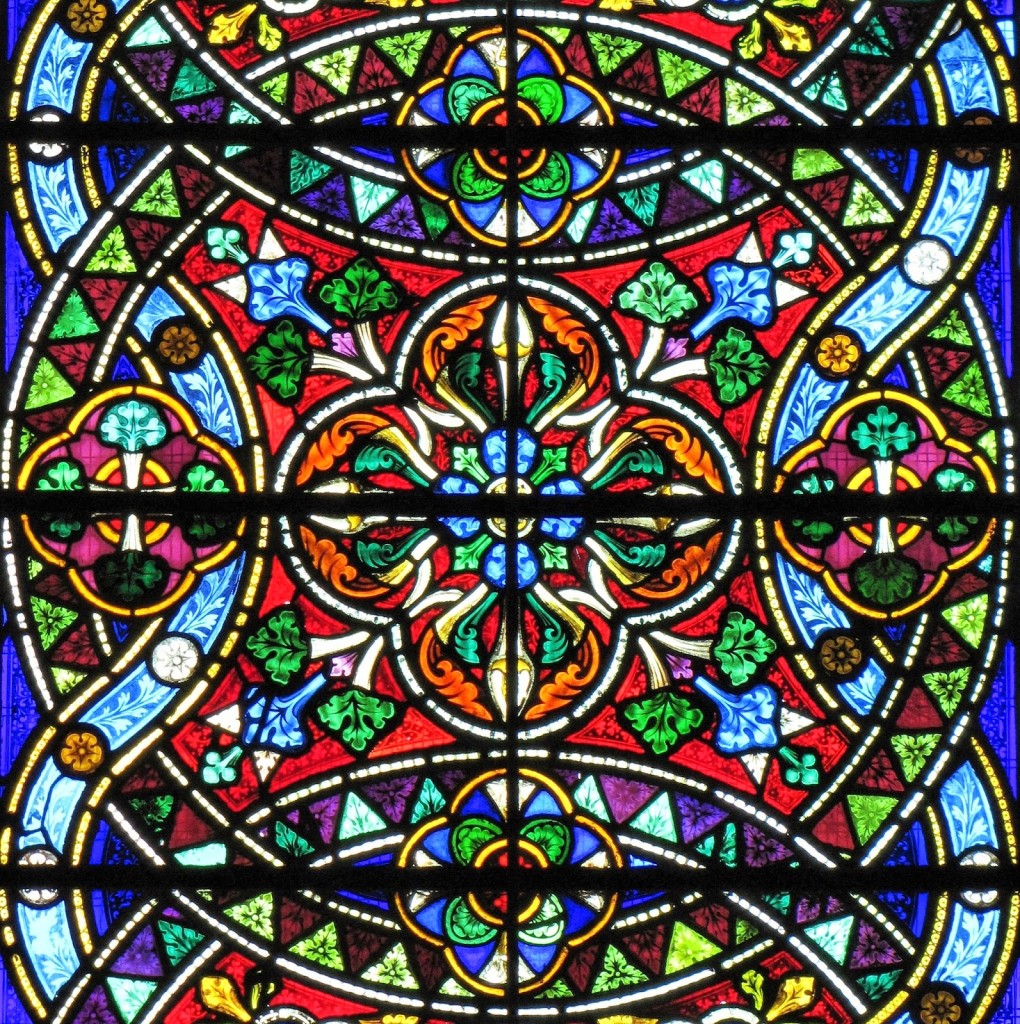

Originally opened in 1890, the building was designed in a Victorian Palladian style by the Cork architects Thomas Newenham Deane and Thomas Manly Deane. The ornate interior is nearly as impressive as the collection itself. In the central court, lacey patterns of cast iron ring the balcony and support the roof like giant, load-bearing doilies, while majolica fireplaces and carved wooden panels ring the walls of other galleries.

We visited the museum towards the end of our first day in Ireland, and my initial jet lag made it difficult to absorb the copious information sprinkled throughout the galleries. If you are awake for it, though, a visit to the museum of Archaeology can be an ideal introduction to the island’s history, artifacts, and sites.

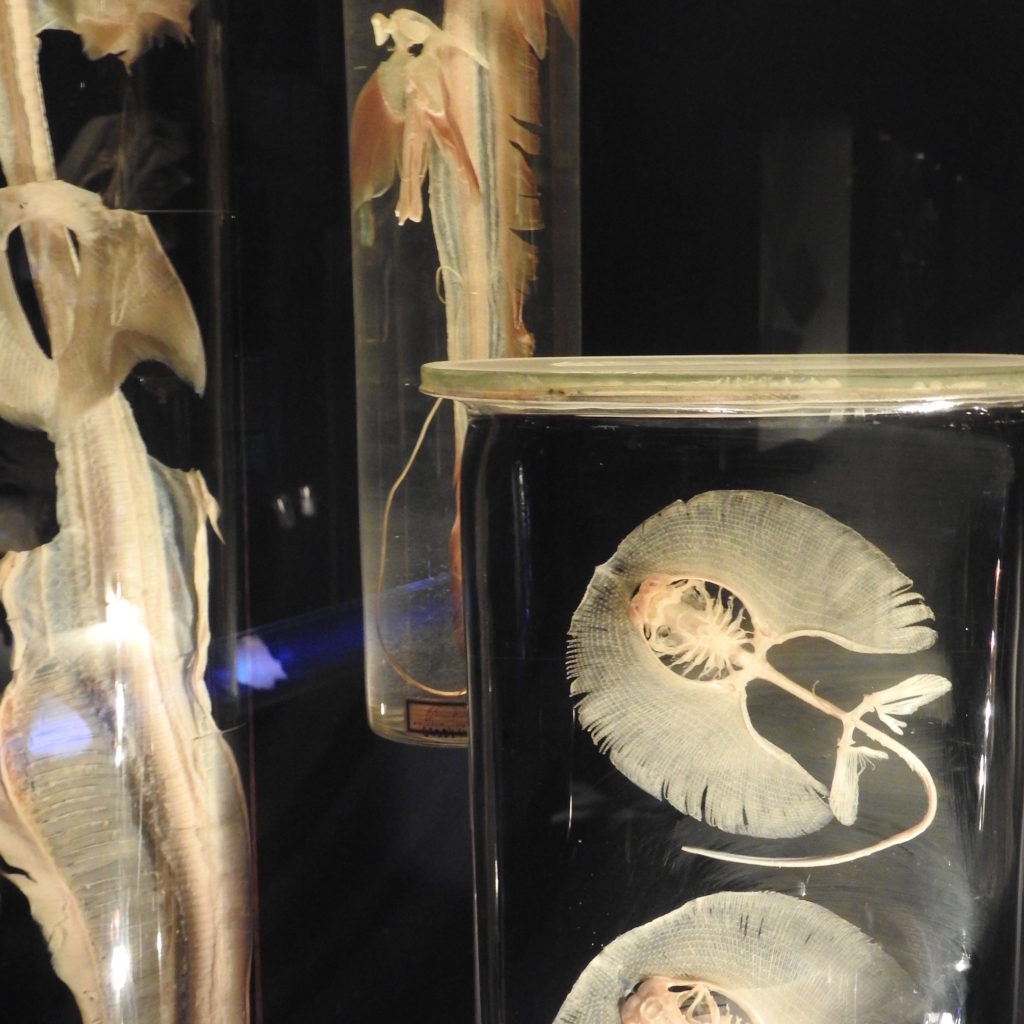

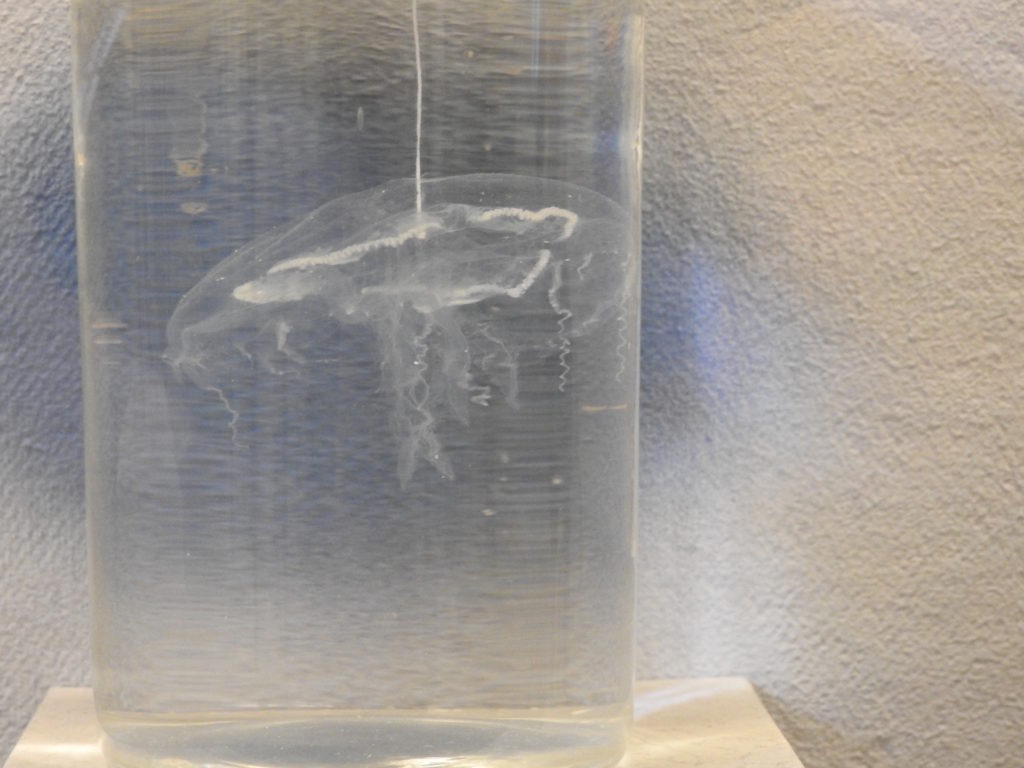

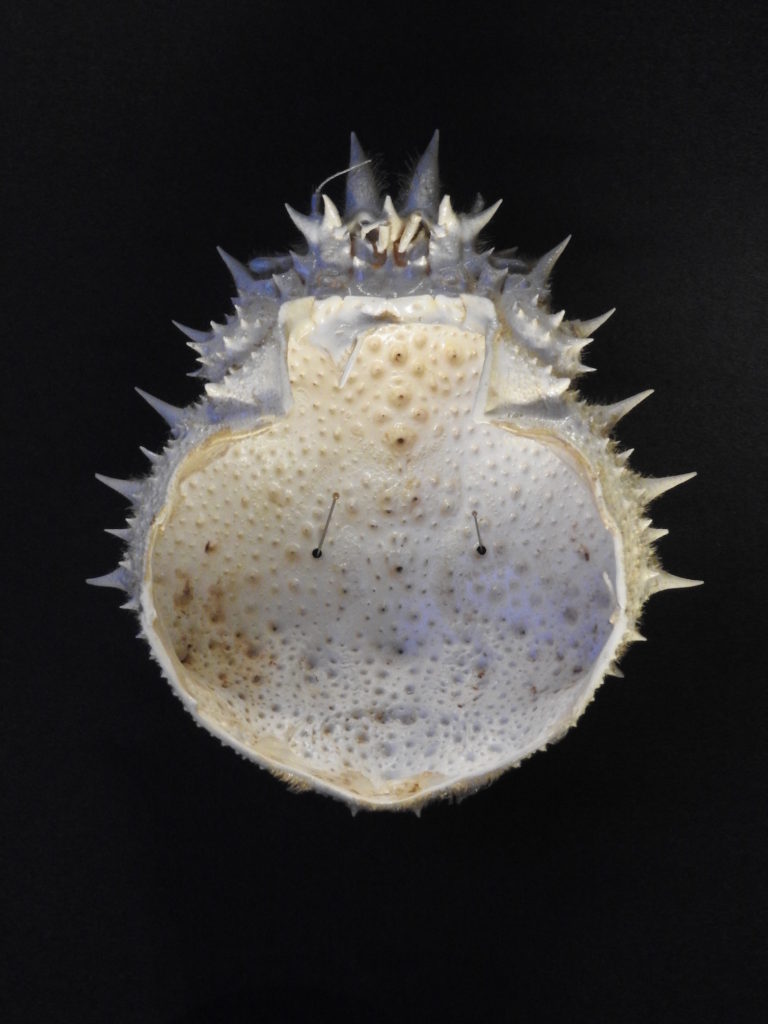

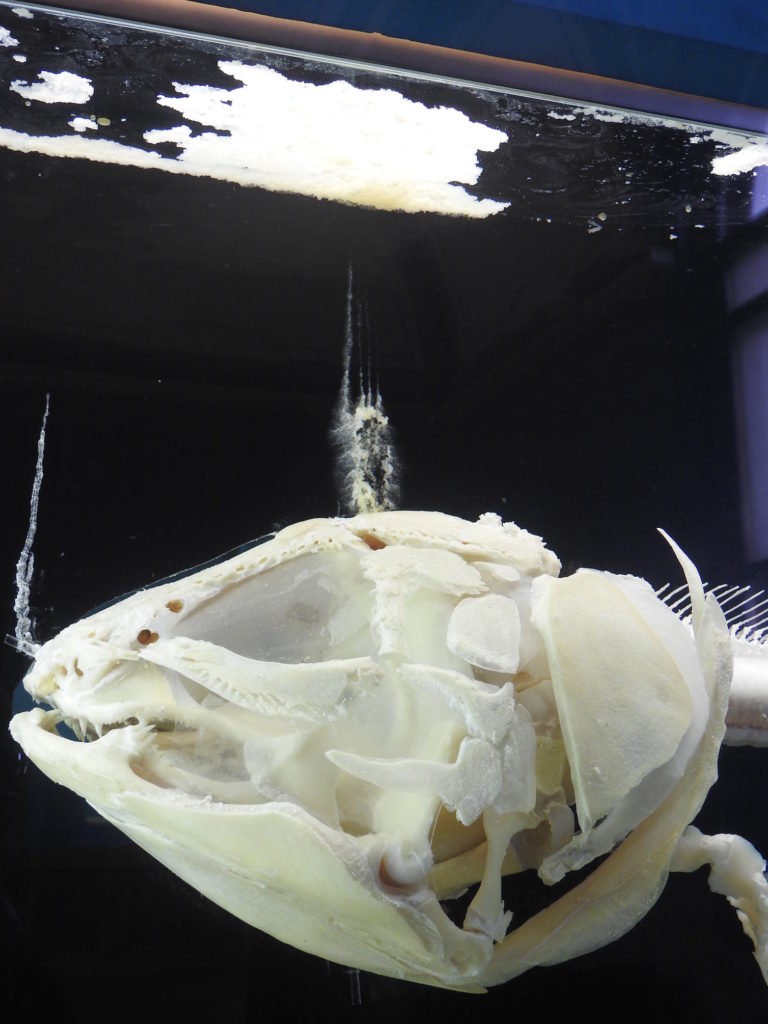

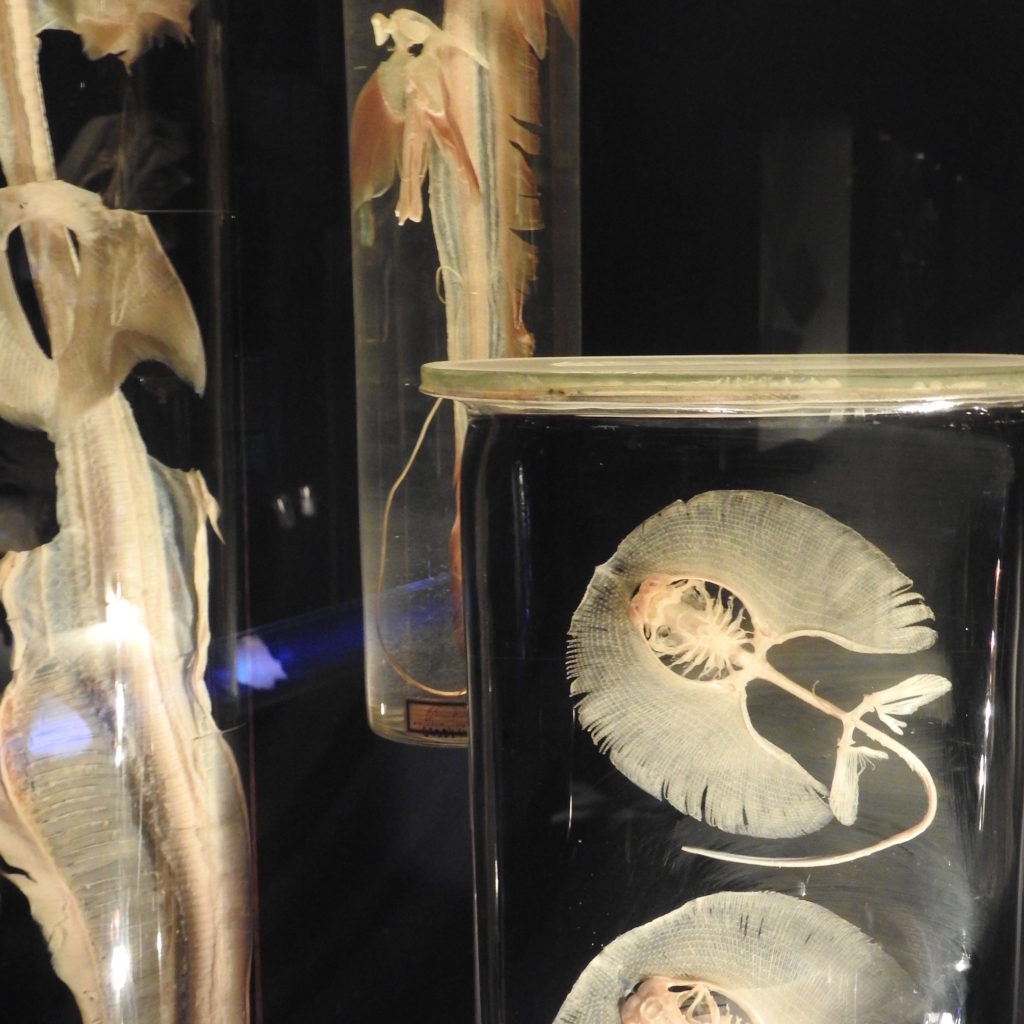

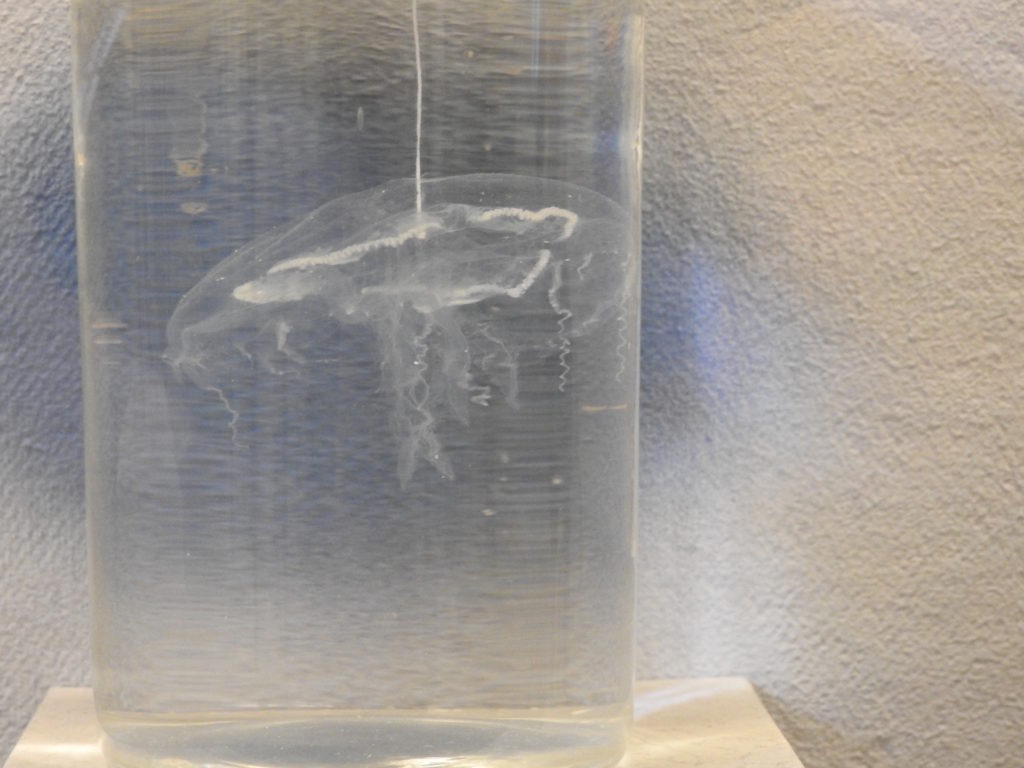

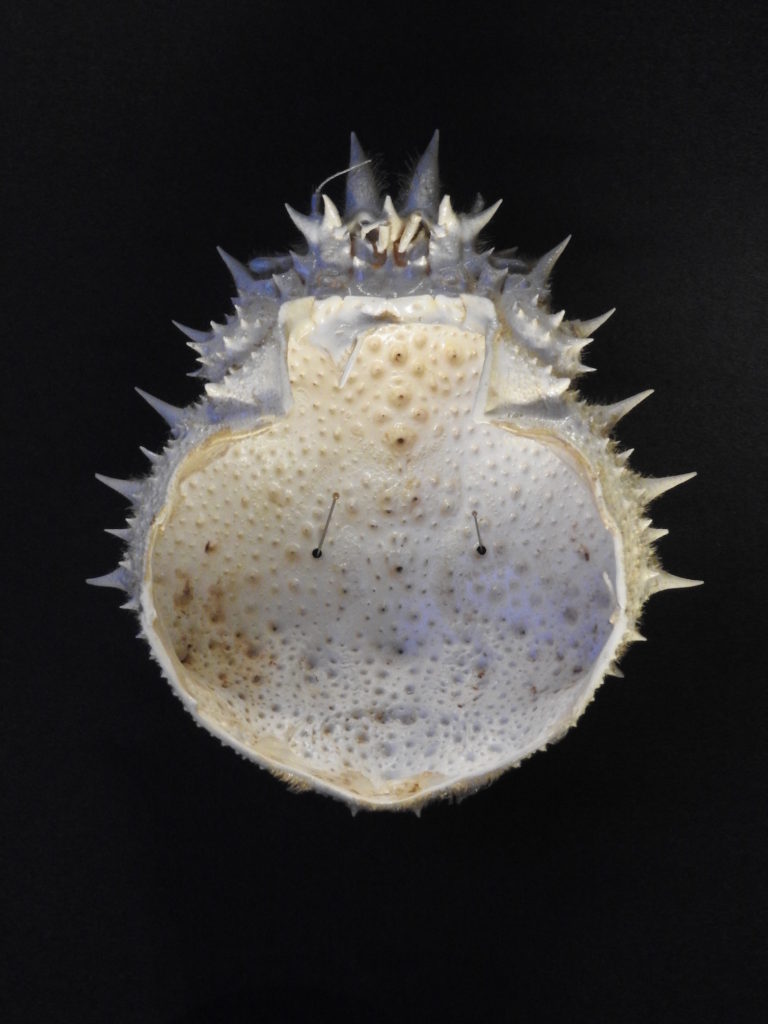

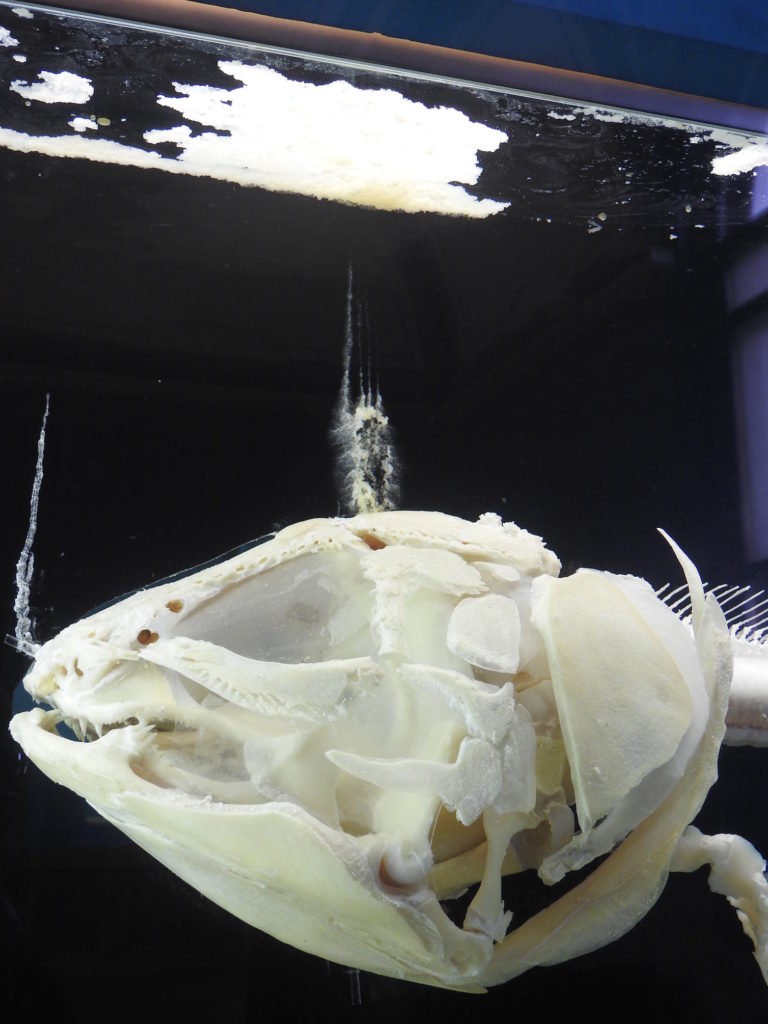

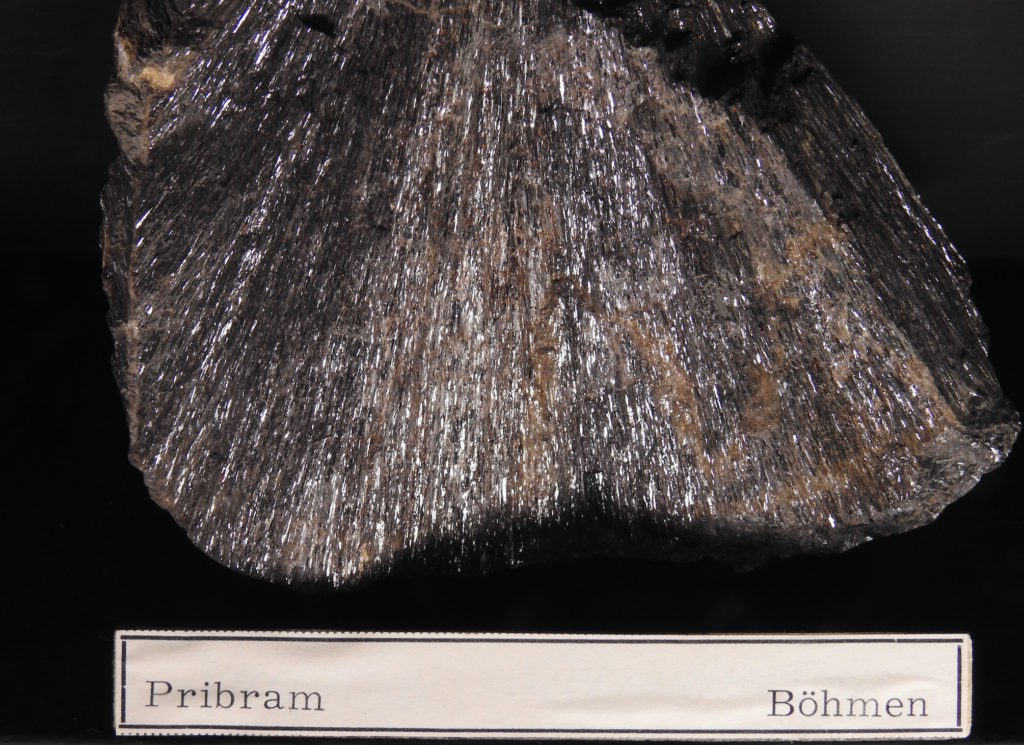

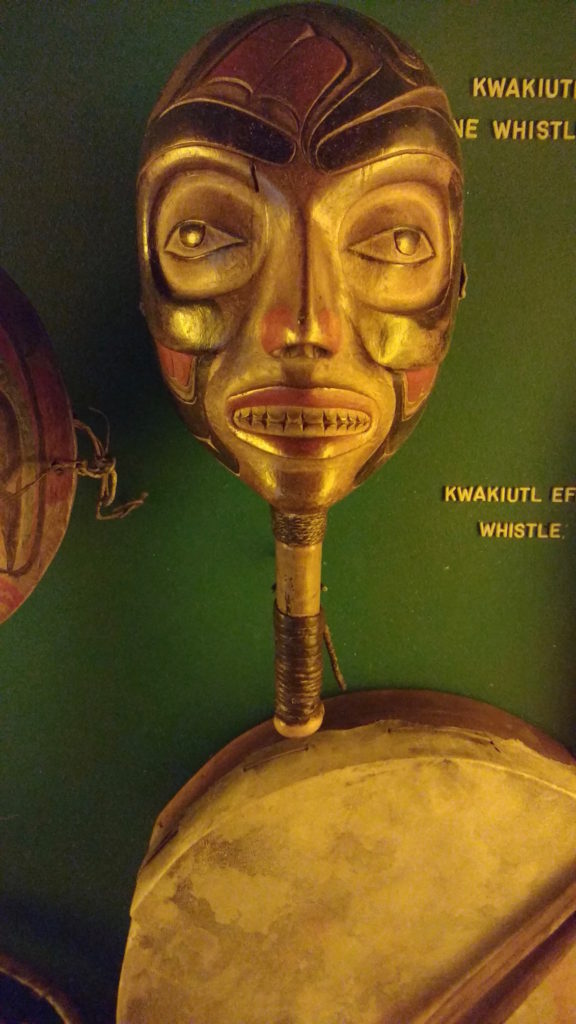

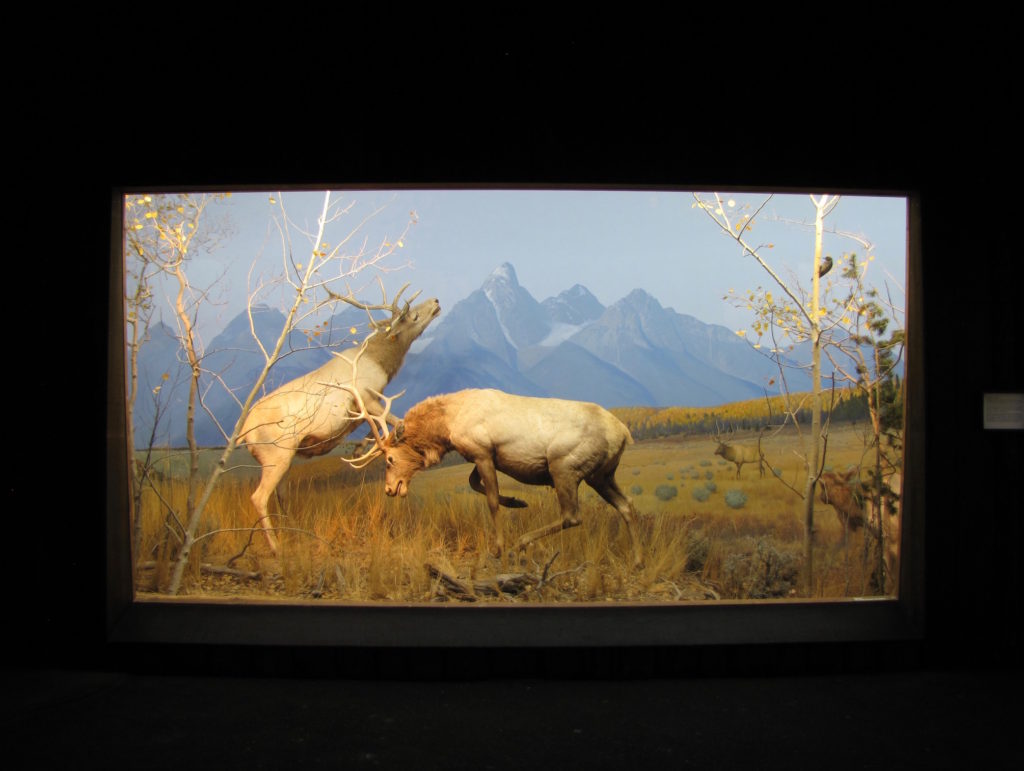

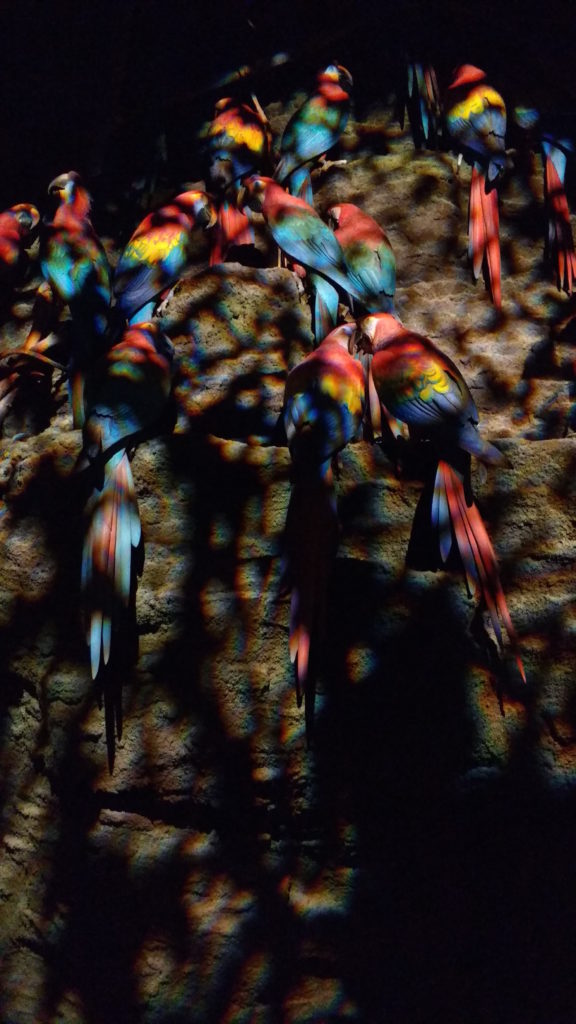

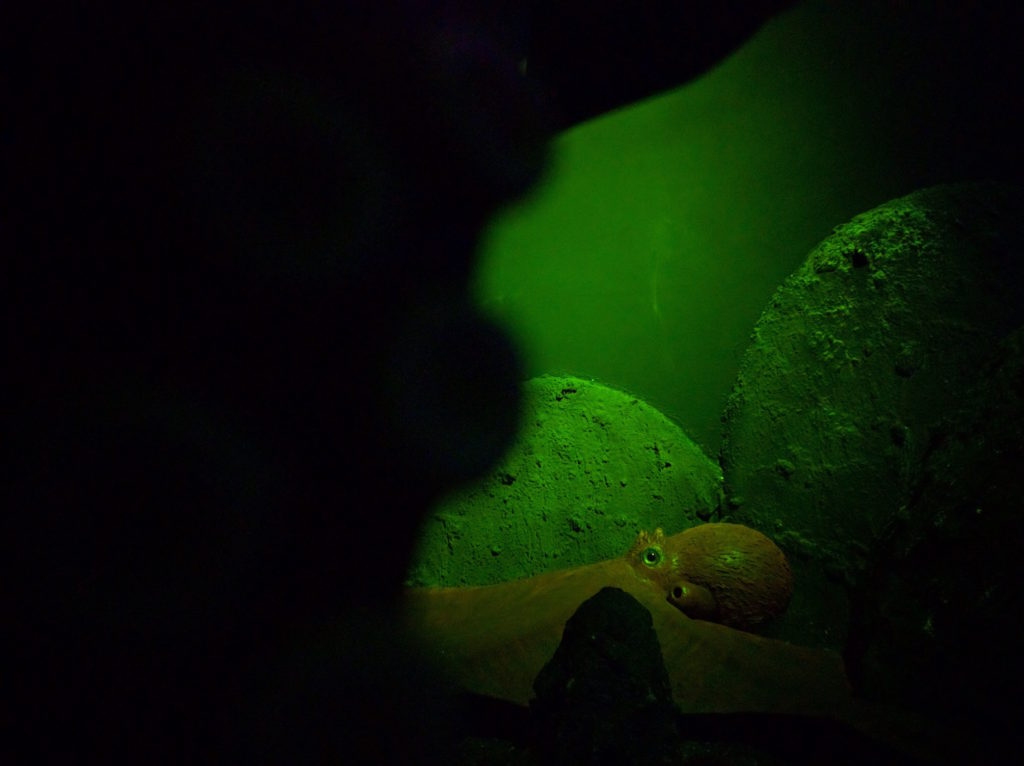

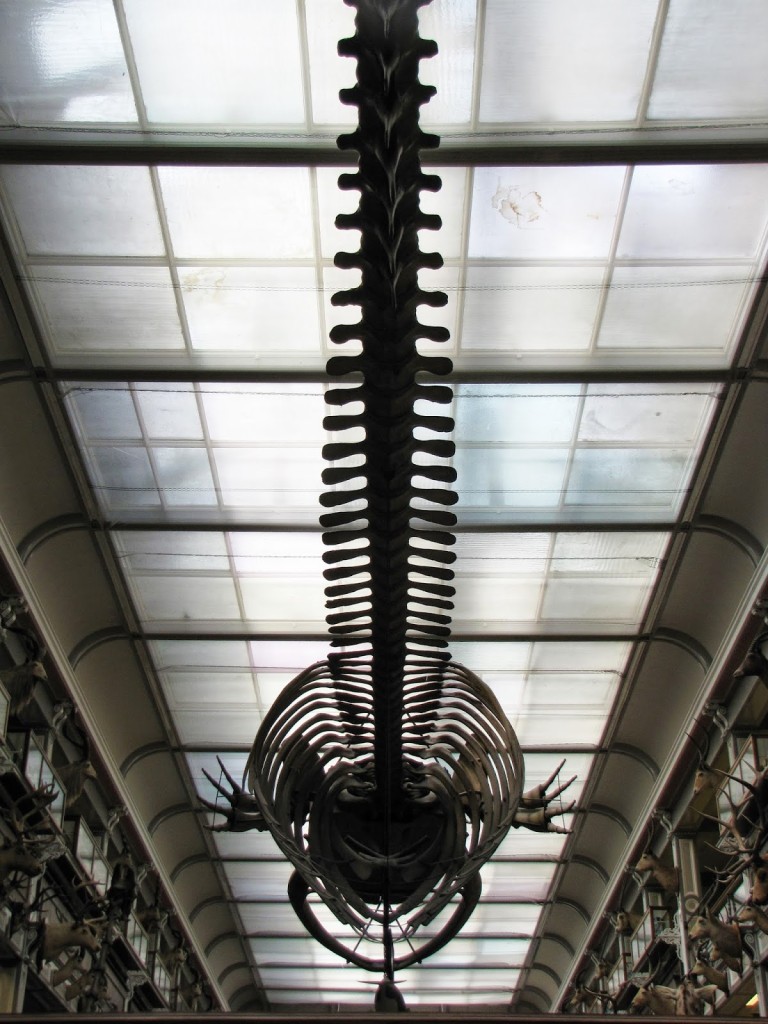

When Ireland’s museum of natural history opened in 1857 with an inaugural lecture by the internationally renowned Scottish explorer, Dr. David Livingstone, Dublin was one of the most important cities of the British Empire. As a result, the museum served as a repository for animal, vegetal, and geological specimens sent back by Britain’s agents from around the globe. Today, the museum looks much the way it did in the 19th century. The building consists of three floors of exhibition space, only two of which are open to the public: the lower floor is dedicated to the flora and fauna of the island, while the second story displays mammals from around the world.

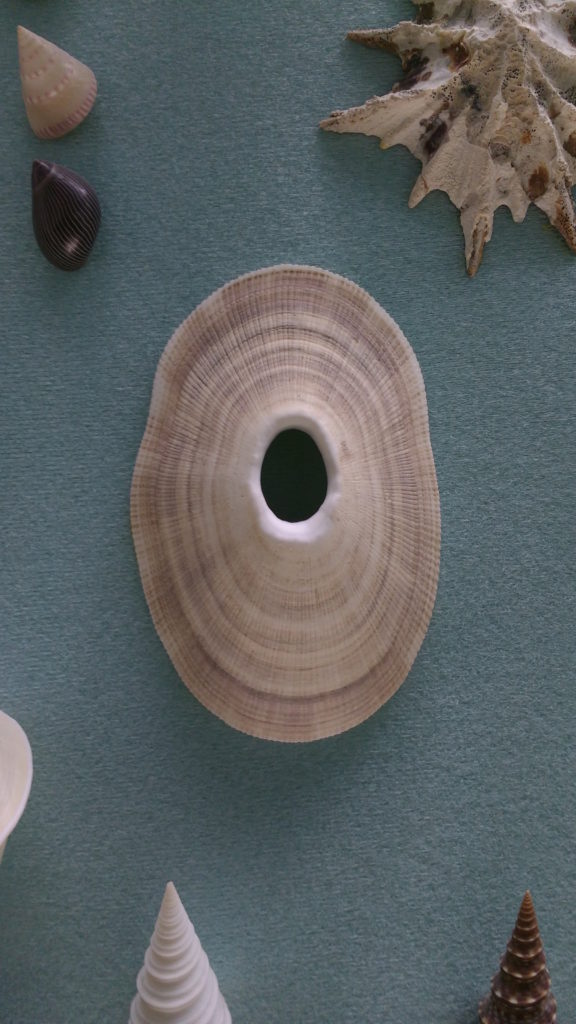

The Natural History Museum predates the founding of the National Museum of Ireland by about 20 years, making it the oldest branch of the NMI. Parts of its original collection have since relocated to other institutions―including the museum of Archaeology―but it still houses a rare collection of life-like sea creatures made by the 19th century glass artists Rudolf and Leopold Blaschka.

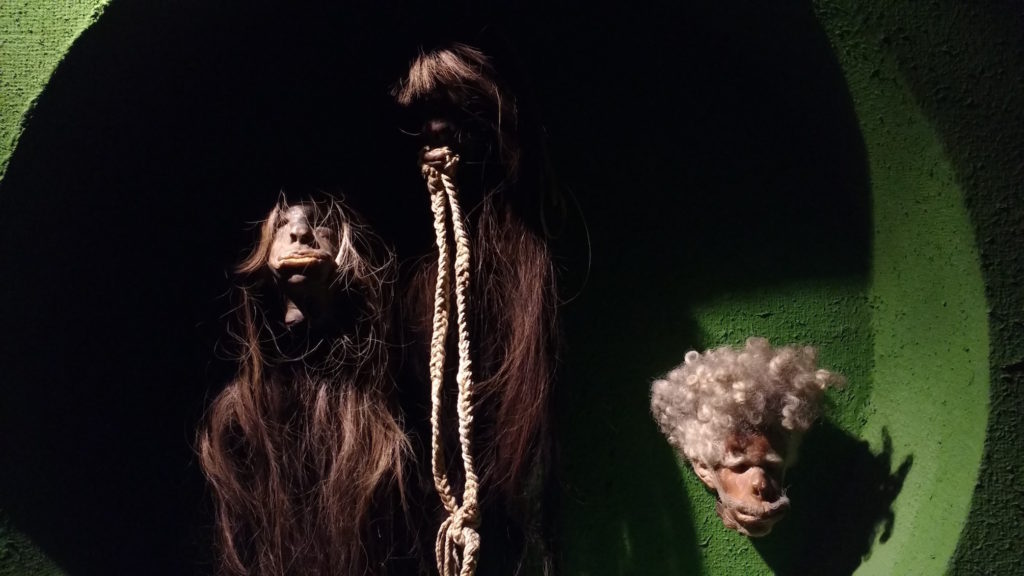

Unfortunately, the institution is woefully underfunded, leaving many of the specimens in tatters and causing the balcony galleries, where the majority of the Blaschkas’ models reside, to close. But the feelings of neglect and loss that permeate the galleries are no less due to the taxidermy and display choices of the past and present curators. In death, many of the animals have been assigned strong personalities, sometimes presented with bared teeth or open mouths, as if silently growling or screaming at the passing visitor. In other, more disturbing, instances, the animals appear to be frightened or startled. In one case, a tiger looks timidly upward, seemingly afraid of its surroundings. In another, a new-born zebra sits alone in its vitrine against a wall. The juxtaposition of the foal’s simulated alertness and innocence with the reality of its death and isolation is particularly disquieting. I could only wonder how it came to be there, and then wish that I hadn’t.

Still, even the more questionable curatorial choices speak to a certain—albeit dark—sense of humor that saves the displays from being purely bleak examples of monetary neglect.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 23, 2013.

If you’re going to Ireland, chances are you will fly in and out of Dublin. The Republic’s capital is a mostly charming city of manageable size with several museums, impressive cathedrals, and numerous drinking establishments. Travelers can see a lot in a short amount of time without sacrificing the enjoyment of simply wandering in a new city. In two days, we drank some good beer, ate some good (Indian) food, and went to six museums, two crypts, two cathedrals, one church, and one library. Someone in a hurry or lodging in a more central part of the city could probably do more.

The related article on the relationship between Surrealism and the Naturhistorisches Museum, “The Art of Displaying Life and Death,” was published in the Spring 2010 edition of Anamesa.

All images under copyright of the author. No reproduction without permission (please).