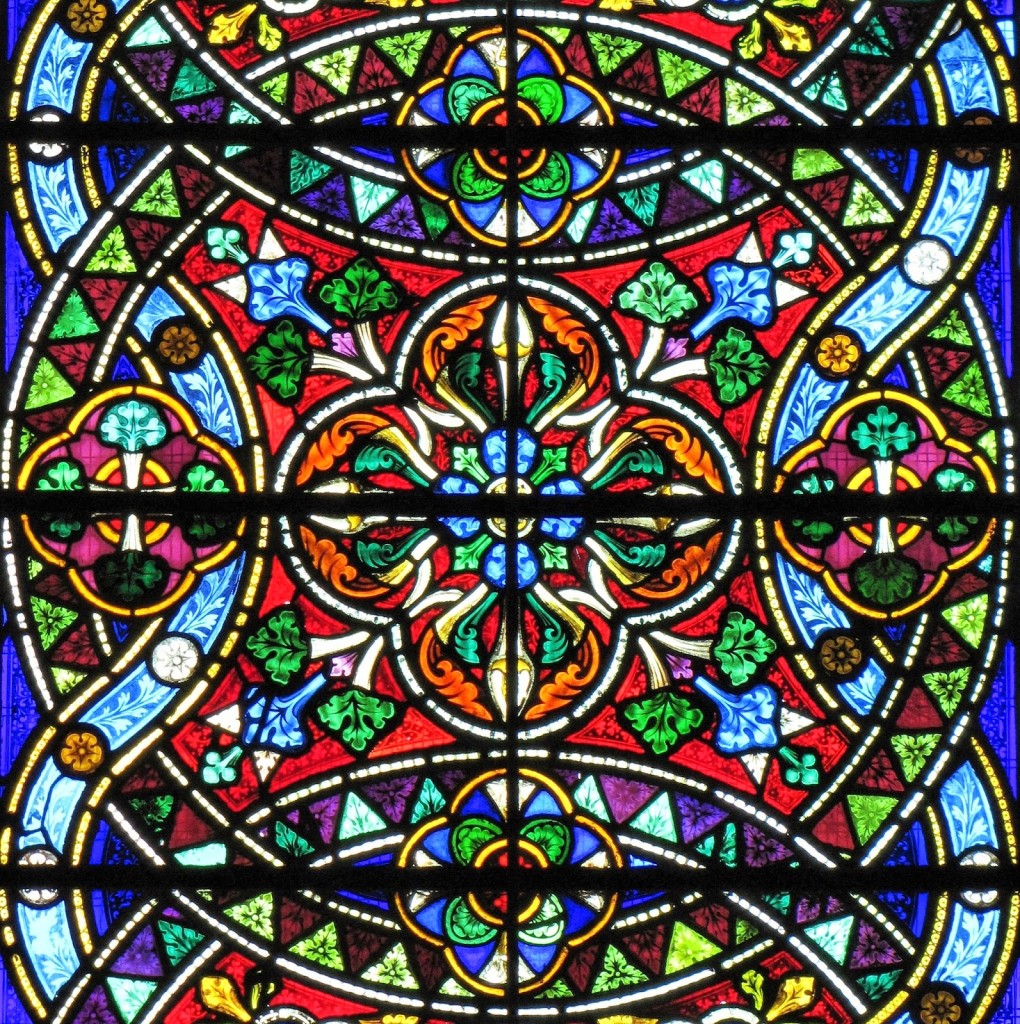

Since the 17th century, Trinity College has been the home of Ireland’s most densely decorated illuminated manuscript, the Book of Kells (c. 9th century). Tourists flock to the College’s Old Library and wait in lines that wrap around Fellow’s Square, just for a peek at a few of the book’s pages.

The related exhibition mostly consists of other manuscripts and reproductions from the Book of Kells interspersed with didactic information. It culminates in a small room containing the original manuscript, now divided into sections so that more of it can be visible at once. The open pages change frequently, but consistently feature both image and script-heavy selections. Photographs are not allowed, and visitors have only a few minutes in the crowded room before they are ushered out. Like a ride at Disneyland, it is hard to argue that the time and money spent trying to see the Book are truly worth the experience. And yet, for anyone at all interested in Celtic design or Medieval art, skipping the Book of Kells is unthinkable.

The same ticket also includes entrance to the Library’s aptly named Long Room, a 210 ft hall containing around 200,000 texts and the Brian Boru Harp. Made around 1220, the harp is the oldest surviving example of its kind in the country and has been prominently featured on the Euro as a symbol of Ireland.

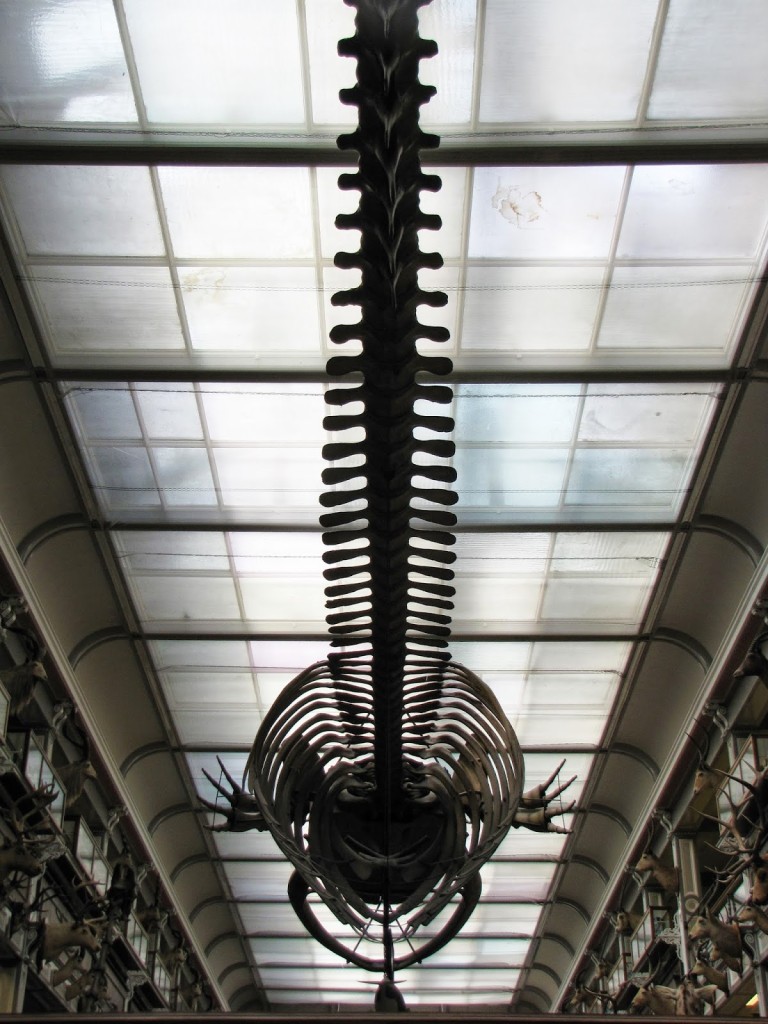

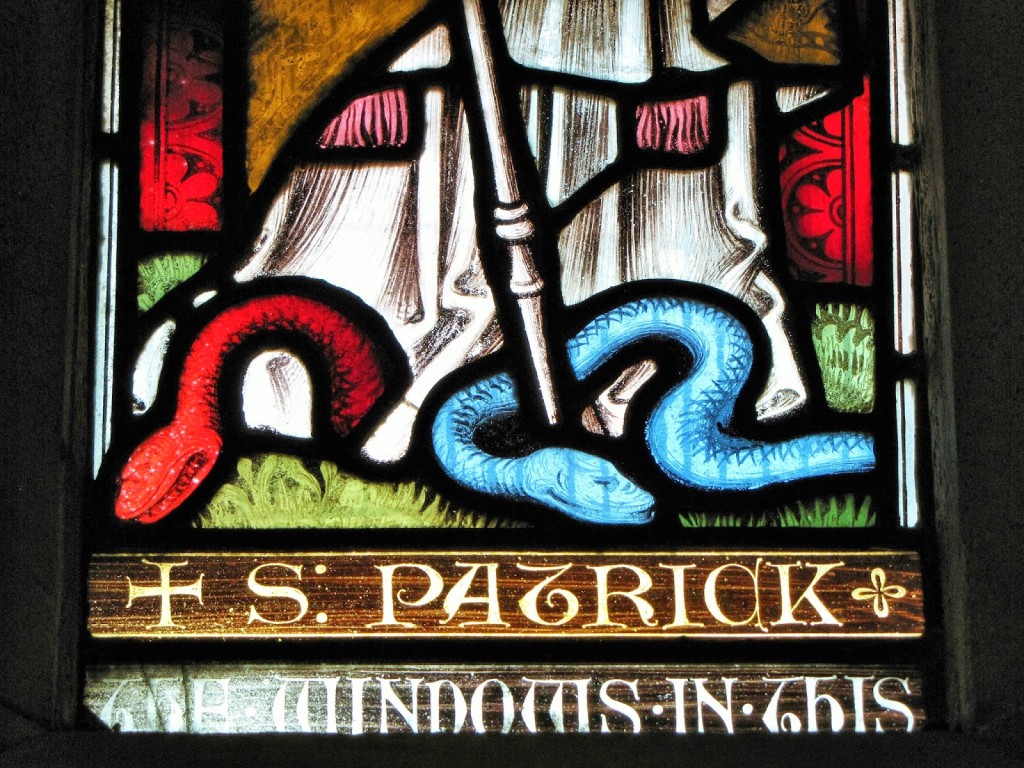

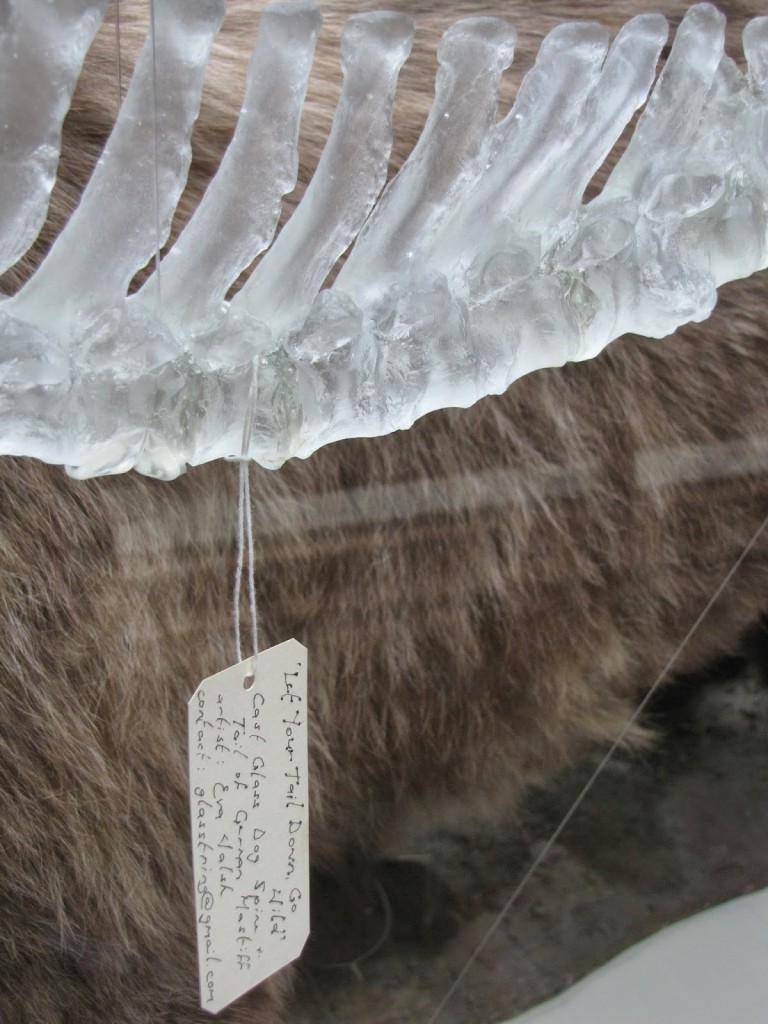

Most tourists only come to the college for the treasures of the Old Library, but a wander around campus can be rewarding. Of particular note, the Museum Building is a Venetian-inspired Victorian structure. Each capital on the building’s exterior consists of a unique and realistic floral design, and these details are carried over into the multicolored marbled decor of the great hall. Upon entering the building, visitors are immediately greeted by the articulated fossilized skeletons of two Giant Irish Elk that seem strangely at home in their stony garden.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 23, 2013.