Photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz and Joshua Albers, August 9, 2014.

Monet, revisited

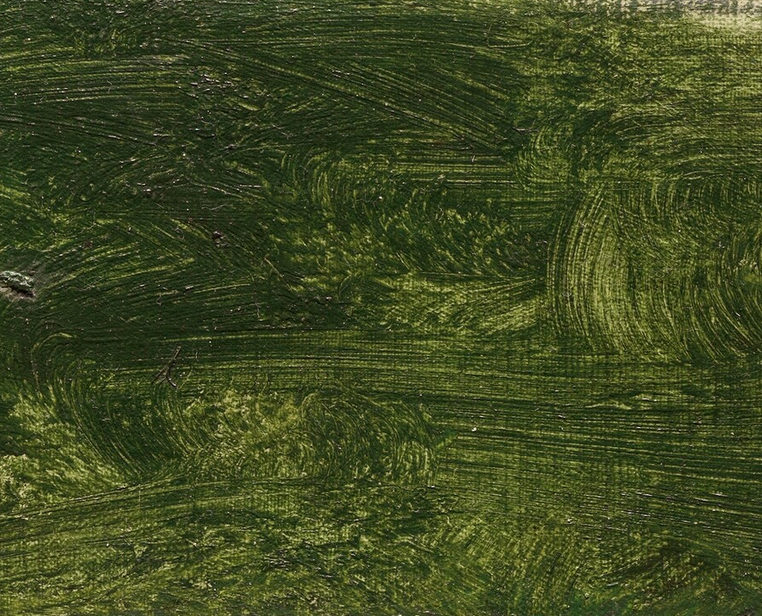

The Art Institute of Chicago recently published the first of several planned online scholarly catalogues based on its collection. This flagship edition focuses on the museum’s paintings and drawings by Monet, and promises to be an incredible free resource for scholars and the mildly curious alike. In addition to contextual essays, technical reports, and extensive documentation, the entries include enlargeable, high-resolution images that allow viewers to see the works in greater detail than would be possible even in the galleries. The following are screenshots of these photographs.

Monet, in my opinion, has never looked so good.

Dublin City Gallery–The Hugh Lane, Dublin, Dublin County, Republic of Ireland

The core collection of Dublin City Gallery–The Hugh Lane is made up of the Impressionist paintings donated by the museum’s namesake, Sir Hugh Lane, to the Dublin Corporation in 1905. At the time, however, the Corporation was unprepared to house the works, and Lane began to look for a more suitable home for his gift. He had already begun transferring paintings to the National Gallery, London, when Dublin proposed Charlemont House as a possible site for the museum. Lane agreed to the new arrangement, but died before his revised will could be witnessed. The result was a nearly 50-year dispute that was eventually resolved with the somewhat awkward arrangement of the two museums swapping the works every five years.

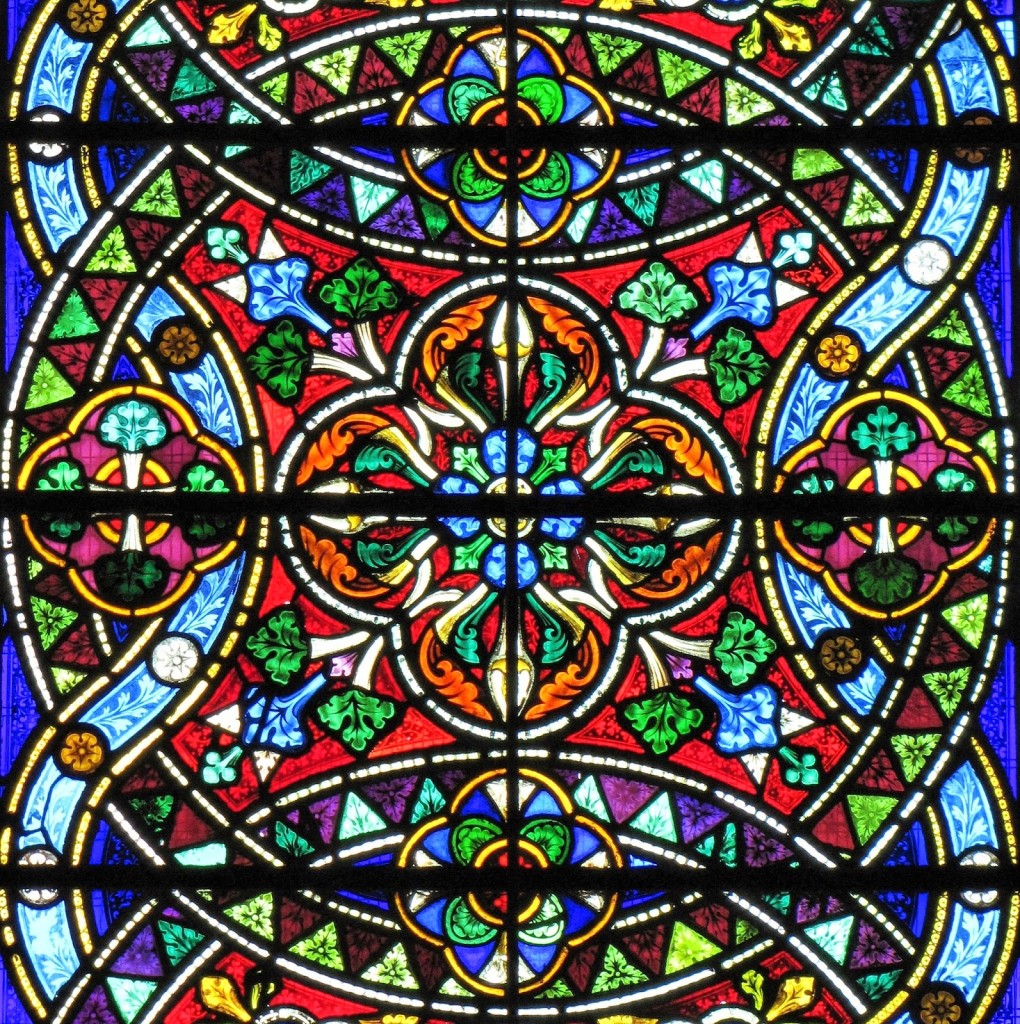

The current collection of the Dublin City Gallery has expanded to include a wide variety of media—from stained glass to digital arts—made by both Irish and international artists throughout the last century-and-a-half. Since 2001, the museum has also served as the new home for Francis Bacon’s former London studio. John Edwards, the bartender/model/companion who inherited Bacon’s estate in 1992, donated the studio’s contents—including its walls, ceiling, floor, and doors—to the Hugh Lane in 1998, and the gallery meticulously reconstructed the room in all its messy glory. The installation is now viewable behind glass windows and through peep-holes.

National Museum of Ireland–Archaeology and Natural History Museum, Dublin, Dublin County, Republic of Ireland

The National Museum of Ireland was originally founded in 1877 when, under the Dublin Science and Art Museum Act, the government purchased the growing collections of Leinster House (now the seat of parliament) and the Natural History Museum. Today, the NMI is divided into four branches: Archaeology, Natural History, Decorative Arts and History, and Country Life. Each branch occupies a separate building, and only the first three are in Dublin. Both the museums of Archaeology and Natural History are located within easy walking distance of Trinity College, the National Gallery, and each other, making it possible to visit all four on the same day.

Archaeology [photography not permitted in most galleries]

The Archaeology branch of the National Museum contains a variety of artifacts—including objects from Rome, Cyprus, and Egypt—although the heart of its collection comes from Ireland itself. The museum’s extensive holdings span prehistory to the Middle Ages. In addition to several of the world’s finest examples of Celtic art, they include one of Europe’s largest collections of prehistoric goldwork and Iron Age bog bodies.

Originally opened in 1890, the building was designed in a Victorian Palladian style by the Cork architects Thomas Newenham Deane and Thomas Manly Deane. The ornate interior is nearly as impressive as the collection itself. In the central court, lacey patterns of cast iron ring the balcony and support the roof like giant, load-bearing doilies, while majolica fireplaces and carved wooden panels ring the walls of other galleries.

We visited the museum towards the end of our first day in Ireland, and my initial jet lag made it difficult to absorb the copious information sprinkled throughout the galleries. If you are awake for it, though, a visit to the museum of Archaeology can be an ideal introduction to the island’s history, artifacts, and sites.

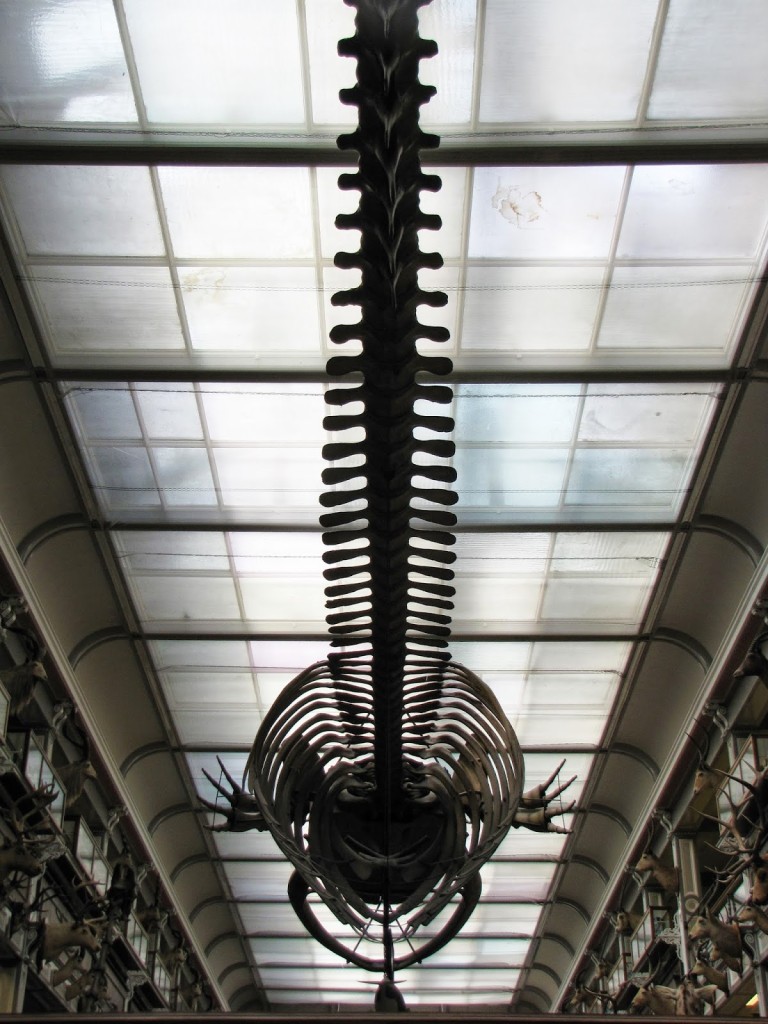

When Ireland’s museum of natural history opened in 1857 with an inaugural lecture by the internationally renowned Scottish explorer, Dr. David Livingstone, Dublin was one of the most important cities of the British Empire. As a result, the museum served as a repository for animal, vegetal, and geological specimens sent back by Britain’s agents from around the globe. Today, the museum looks much the way it did in the 19th century. The building consists of three floors of exhibition space, only two of which are open to the public: the lower floor is dedicated to the flora and fauna of the island, while the second story displays mammals from around the world.

The Natural History Museum predates the founding of the National Museum of Ireland by about 20 years, making it the oldest branch of the NMI. Parts of its original collection have since relocated to other institutions―including the museum of Archaeology―but it still houses a rare collection of life-like sea creatures made by the 19th century glass artists Rudolf and Leopold Blaschka.

Unfortunately, the institution is woefully underfunded, leaving many of the specimens in tatters and causing the balcony galleries, where the majority of the Blaschkas’ models reside, to close. But the feelings of neglect and loss that permeate the galleries are no less due to the taxidermy and display choices of the past and present curators. In death, many of the animals have been assigned strong personalities, sometimes presented with bared teeth or open mouths, as if silently growling or screaming at the passing visitor. In other, more disturbing, instances, the animals appear to be frightened or startled. In one case, a tiger looks timidly upward, seemingly afraid of its surroundings. In another, a new-born zebra sits alone in its vitrine against a wall. The juxtaposition of the foal’s simulated alertness and innocence with the reality of its death and isolation is particularly disquieting. I could only wonder how it came to be there, and then wish that I hadn’t.

Still, even the more questionable curatorial choices speak to a certain—albeit dark—sense of humor that saves the displays from being purely bleak examples of monetary neglect.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 23, 2013.

Trinity College, Dublin, Dublin County, Republic of Ireland

Since the 17th century, Trinity College has been the home of Ireland’s most densely decorated illuminated manuscript, the Book of Kells (c. 9th century). Tourists flock to the College’s Old Library and wait in lines that wrap around Fellow’s Square, just for a peek at a few of the book’s pages.

The related exhibition mostly consists of other manuscripts and reproductions from the Book of Kells interspersed with didactic information. It culminates in a small room containing the original manuscript, now divided into sections so that more of it can be visible at once. The open pages change frequently, but consistently feature both image and script-heavy selections. Photographs are not allowed, and visitors have only a few minutes in the crowded room before they are ushered out. Like a ride at Disneyland, it is hard to argue that the time and money spent trying to see the Book are truly worth the experience. And yet, for anyone at all interested in Celtic design or Medieval art, skipping the Book of Kells is unthinkable.

The same ticket also includes entrance to the Library’s aptly named Long Room, a 210 ft hall containing around 200,000 texts and the Brian Boru Harp. Made around 1220, the harp is the oldest surviving example of its kind in the country and has been prominently featured on the Euro as a symbol of Ireland.

Most tourists only come to the college for the treasures of the Old Library, but a wander around campus can be rewarding. Of particular note, the Museum Building is a Venetian-inspired Victorian structure. Each capital on the building’s exterior consists of a unique and realistic floral design, and these details are carried over into the multicolored marbled decor of the great hall. Upon entering the building, visitors are immediately greeted by the articulated fossilized skeletons of two Giant Irish Elk that seem strangely at home in their stony garden.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 23, 2013.

Impressions of Dublin

If you’re going to Ireland, chances are you will fly in and out of Dublin. The Republic’s capital is a mostly charming city of manageable size with several museums, impressive cathedrals, and numerous drinking establishments. Travelers can see a lot in a short amount of time without sacrificing the enjoyment of simply wandering in a new city. In two days, we drank some good beer, ate some good (Indian) food, and went to six museums, two crypts, two cathedrals, one church, and one library. Someone in a hurry or lodging in a more central part of the city could probably do more.

Great Rivers Biennial at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis

Throughout the long modern period, from the Renaissance to Jasper Johns, the visual arts have perpetually defined themselves against each other, even while endeavoring to simultaneously transgress their self-imposed boundaries. The advent of photography in the 19th century brought new urgency to these conceptual games, when for the first time painting, long held as art’s regent medium, had to prove its worth against a new technology that threatened to replace it. Of course, rather than rendering painting obsolete, photography ultimately freed the older medium from an obsession with mimesis and helped to usher in the styles of modernity that have come to define art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Impressionism, Expressionism, and even Cubism.

Now, the advent of digital arts—that newest of new media—has created a fresh challenge to more traditional materials. In its seeming immateriality, digital art possesses a fluid, transmittable bodylessness that is not only of the present (and future) moment, but that promises to be an accessible and democratic art form capable of circumventing the current insanity and inherent classism of the art market. As a result, the question facing contemporary painters and sculptors is no longer, “Why does my particular media matter?” but rather, “Why does art in any traditional media matter?”

The current Great Rivers Biennial at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis faces this challenge head-on by featuring three St. Louis-based artists who are deeply invested in materiality. They are, in fact, most clearly linked by their shared and unapologetic determination that matter matters. And each, in her or his own way, makes a strong case for the continued singularity of experiencing the physicality of objects.

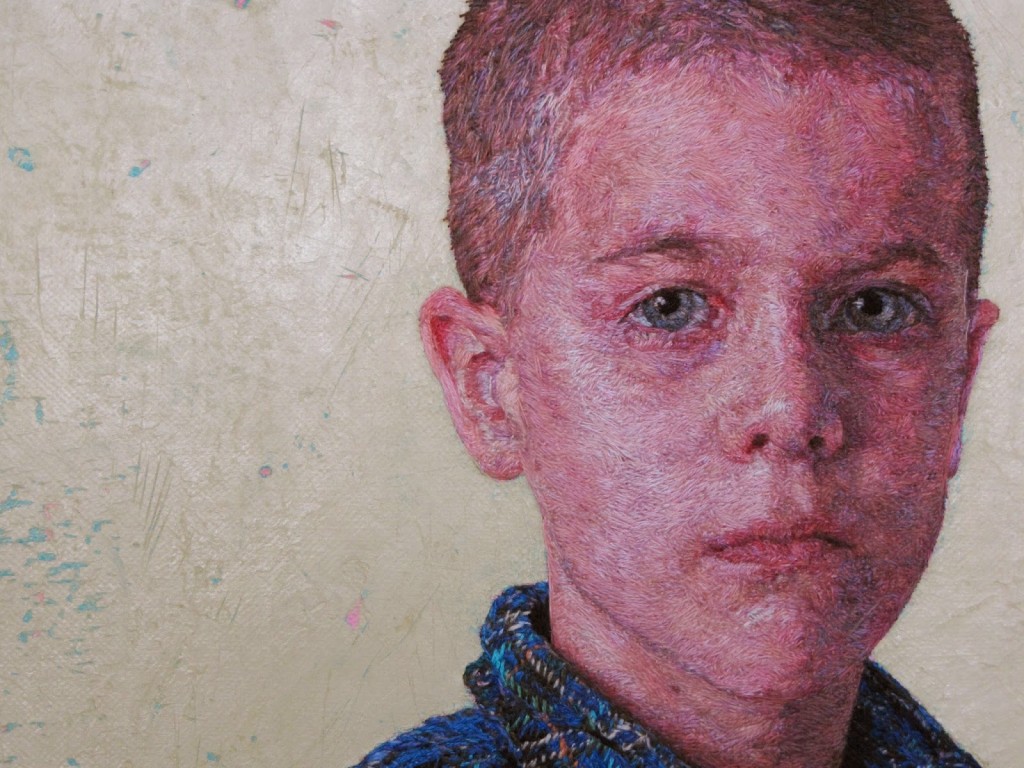

Cayce Zavaglia, Recto/Verso

In the aptly titled Recto/Verso, Cayce Zavaglia presents a series of embroidered portraits of friends and family alongside large-scale paintings depicting the backs of these textiles. While the embroidered pictures exquisitely and affectionately render their subjects in detailed, delicate realism, the paintings physically and psychologically dominate the gallery with their frenetic, abstracted surfaces. Although the paintings are in fact one step further removed from the people who inspired the original images, they seem to offer a more incisive and complex reading of their human subjects.

In both media, Zavaglia’s works also deal with a second, more subtle theme: that of the relationship between embroidery and painting. While the paintings are clearly based on her textiles, the textiles are equally indebted to the appearance of paintings. Portraiture is traditionally under the purview of painting, and Zavaglia has played with this expectation in her embroidery by creating stitching that closely resembles the marks of a paint brush. The textiles and paintings therefore resonate against each other through both their shared subjects and the interrelatedness of their media.

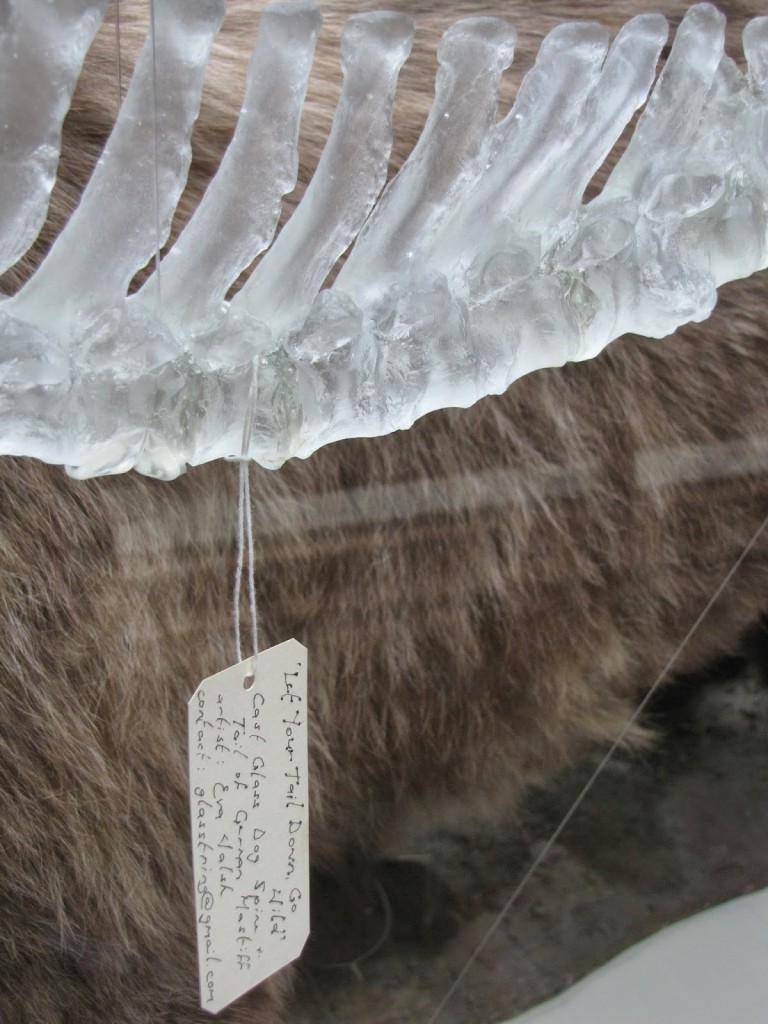

Carlie Trosclair, Exfoliation

For Exfoliation, Carlie Trosclair filled CAMStL’s central gallery with an open structure of flayed walls. Ragged-edged gaps in drywall frame vintage wallpapers and salvaged beams like an open wound pulled back to reveal another, even more damaged layer of skin hiding beneath the bone. Completing the immersive installation, Trosclair partially wallpapered the opposite wall and then proceeded to redefine the paper’s repeating pattern by carefully excising portions of the design, removing some areas completely and allowing others to curl towards the floor like mossy tendrils. Her unbuilt-constructions, broadly reminiscent of both geological fissures and abandoned hotels, play with notions of interior and exterior, nature and architecture, creation and decay, permanence and impermanence. And although her work is an almost pure meditation on materiality, it also circumvents the marketplace by being explicitly temporary, without a life (as art) after the show ends.

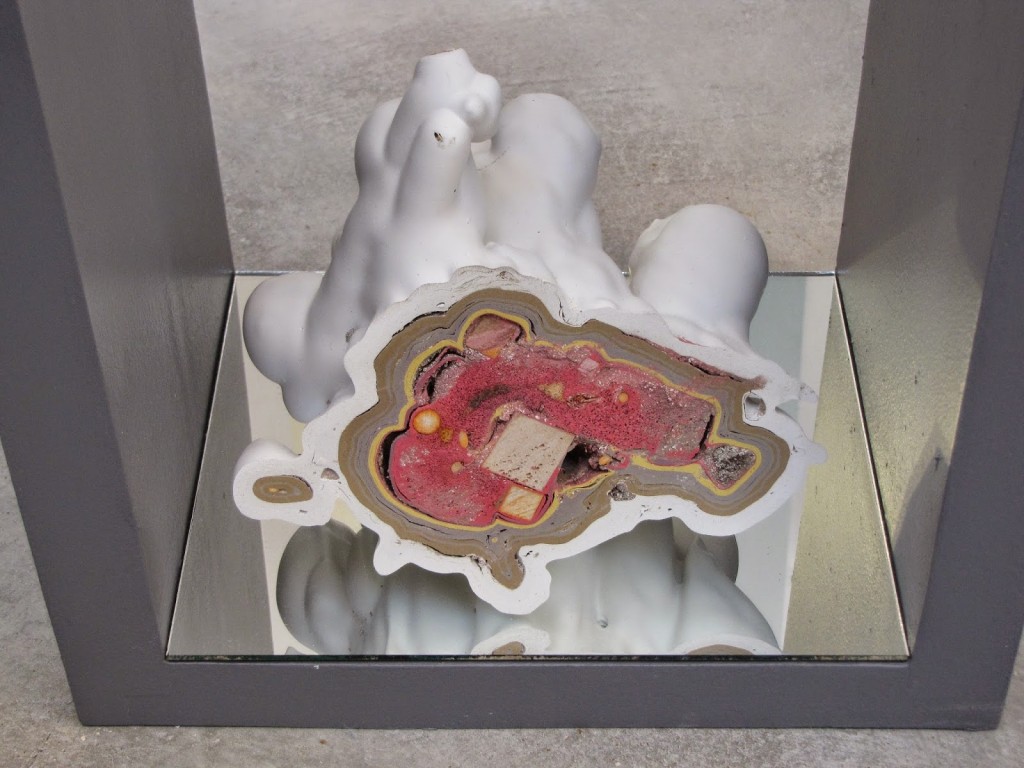

Brandon Anschultz, Suddenly Last Summer

Inspired in part by Tennessee Williams’s play, Suddenly Last Summer, Brandon Anschultz’s installation of the same name consists of multiple, semi-architectural structures supporting biomorphic objects made from layers of paint built up over studio detritus, like sponge and pieces of wood. This is smart work smartly exhibited, with Anschultz’s deceptively playful shapes and hues drawing the viewer into a world filled with darker dramatic tensions. Within each vignette, the colorful, zig-zagging scaffolding and mirrored surfaces frame the paint-objects, multiplying and restricting the visitor’s views in a way that is both generous and withholding, while the luscious tactile quality of the objects similarly taunts the onlooker who is unable—due either to physical hindrances or in deference to accepted museum behavior—to touch them. The installation thus cultivates a sensation of repressed longing that resonates with the tenor of Williams’s mediation on sexuality from the late 1950s.

With their surrealist nod to the erotic potential of abstract but suggestive objects, Brancusian play between support and sculpture, and concern with controlled but multiple viewpoints, Anschultz’s installations are clearly indebted to the history and concerns of sculpture, even as they represent a particular fascination with the physical qualities of paint. More than yet another reinvention of painting, however, his works—like those of his co-exhibitors—both celebrate and reaffirm the importance of materiality in art at a time when such affirmation is as welcome as it is necessary.

The Great Rivers Biennial opened on May 9 and will run until August 10, 2014 at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz.

Swoon: Submerged Motherlands at the Brooklyn Museum of Art

Fusing the aesthetics of an art-school education with the environmental immediacy of street art, Swoon has come to fame in the last few years for her large, intricate, wheat-pasted prints, urban interventions, and community-based projects. Submerged Motherlands brings her practice indoors in order to create a new, immersive environment within the Brooklyn Museum’s 5th floor rotunda gallery. Look up, look down, stand back, plunge in—the installation encourages a thorough investigation of its many nooks and crannies, and rewards the viewer at every angle.

Swoon: Submerged Motherlands will be on view until August 24, 2014. For more information, visit the Brooklyn Museum’s website.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 4, 2014.

New York, May 2014

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 2–4, 2014.

Jerpoint Abbey, County Kilkenny, Republic of Ireland

Jerpoint Abbey was once an important Cistercian monastery and a favorite burial site for the area’s powerful families. Its general biography is fairly familiar: founded in the mid-late 12th century, it flourished until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539 and soon after passed into the secular hands of James Butler, Earl of Ormonde.

[A more detailed history of the abbey can be found here, courtesy of the Cistercians in Yorkshire Project.]

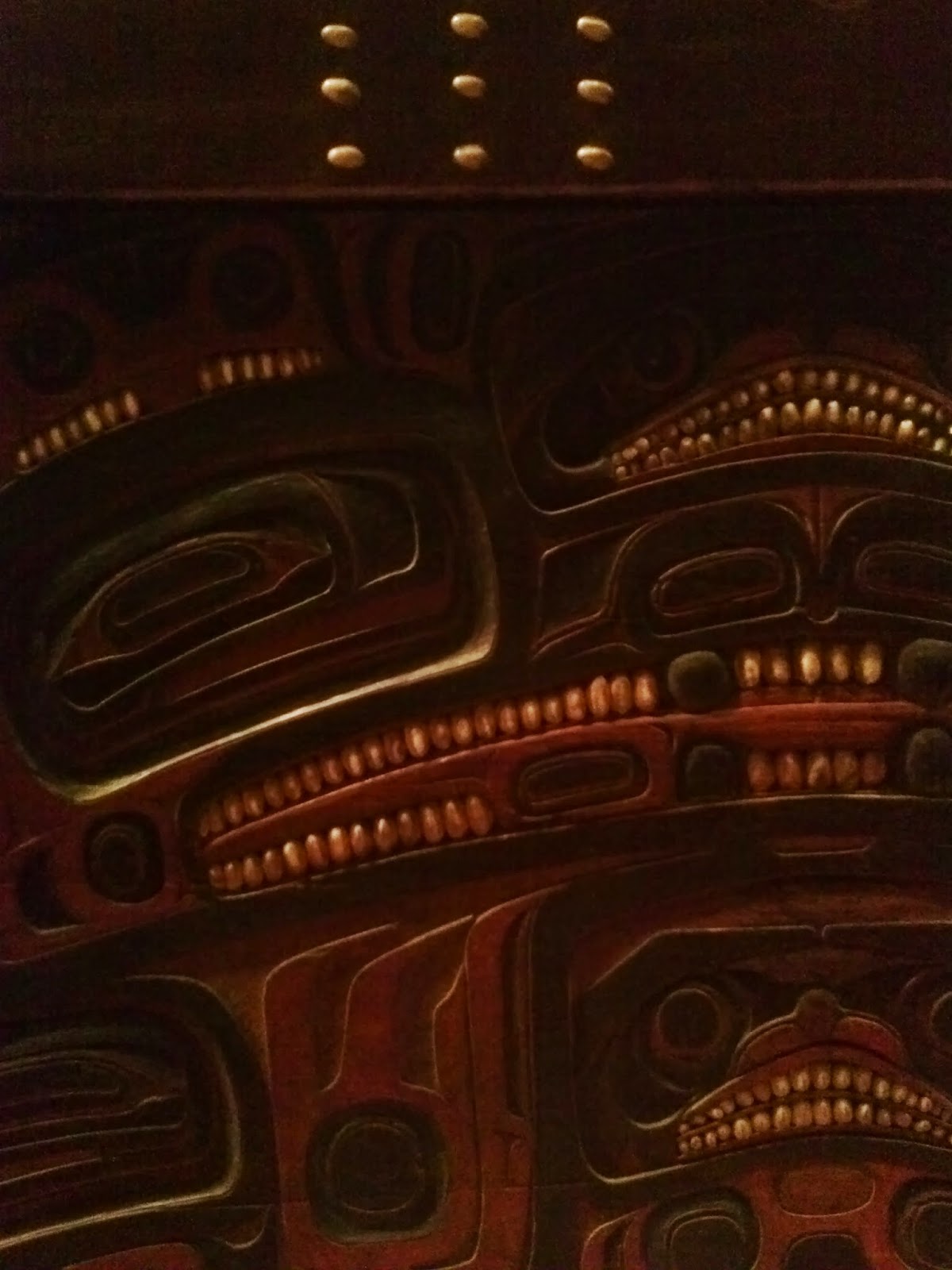

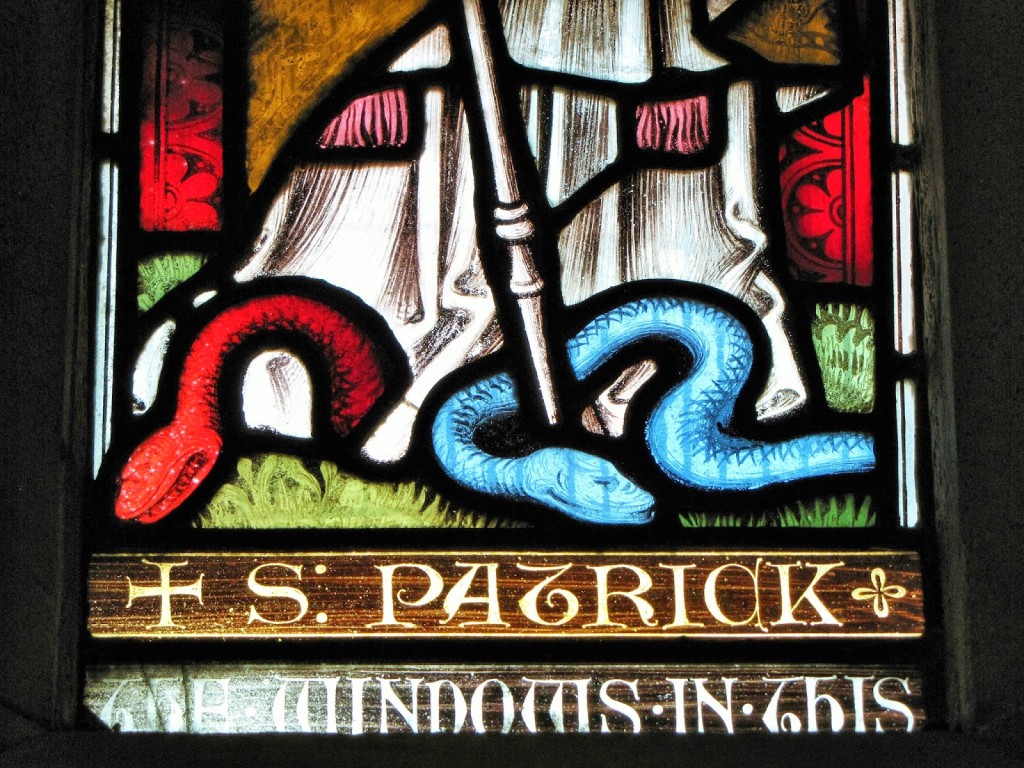

Much of the church is still standing, with highlights including several ornately carved 16th-century tombs and a fortified crossing tower. However, the site’s primary draw is its unique but heavily damaged 15th-century cloister, which was partially reconstructed in the 1950s. Each of the remaining pillars consists of two simple columns framing, on the better preserved examples, large, high-relief images of saints and various medieval personages. Dragons, green men, and other grotesque or humorous figures also appear along the colonnade and under the connecting arches.