The following is an edited-down version of a research paper I wrote in 2009. I did not obtain permission to post the original images of the overall vitrine and its components, so they do not appear here.

Like all objects in museum collections, the work of Joseph Beuys requires conservators and curators to concern themselves with two related, overarching issues: the preservation of the object’s materiality and the preservation of its intellectual content. However, the intentionally mythic nature which underscores much of Beuys’s oeuvre complicates these typical conservation matters in unique and challenging ways. By calling into question the role of the museum and its responsibilities to the artist as well as the public, works by Beuys raise issues that are as basic and as broad as what it means to preserve and present objects “truthfully.”

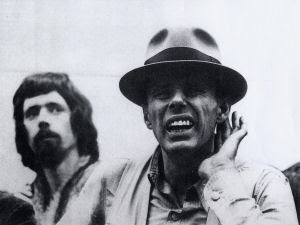

Over the course of his career, Beuys developed a reputation as an artist, teacher, political activist, philosopher, mystic, and shaman who sought to heal society and the psychic wounds of post-WWII Germany by merging art with science, politics, and life. Prolific and controversial, he is still generally accepted as the most influential artistic personality of post-War Germany. Although traditionally trained in sculpture at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf—to which he later returned to teach—Beuys’s preoccupation with personal symbolism and the metaphoric potential of materials led to his use of hitherto unusual media, including fat, felt, butter, and taxidermied hares. Indeed, it is this metaphoric relationship to media that has most clearly been integrated into the production of younger generations of artists.

Beuys rooted his artistic philosophy in a now infamous story based on his experience during World War II. In 1944, less than a year after informing his family of his plans to become an artist, Beuys’s plane was shot down on the Crimean Front. His pilot was killed and Beuys was badly injured. According to the story, a band of Tartars found him and, without regard to his role as a fighting member of the Luftwaffe, nursed him back to health by covering him in fat and wrapping him in felt. Although unconscious during his twelve days in their care, Beuys recalled hearing the word for water, “Voda,” and breathing in the thick smells of cheese, milk, and fat which somehow managed to penetrate his sleeping consciousness. Beuys credited the Tartars, along with the warm, healing potential of fat and felt, with saving his life. As a result, fat, felt, and milk products highlight prominently in his work as generative, primordial materials, while the Tartars became a model for the mythical Eurasian people which figure throughout the artist’s oeuvre.[i]

This story has been so often repeated and is so clearly intrinsic to Beuys’s artistic and social philosophies that it was not seriously questioned until Benjamin Buchloh’s damning ArtForum article in 1980, more than 35 years after the supposed event. Although he was badly injured in a plane crash during a military operation, Beuys was found the next day by a German search commando and recovered in a military hospital.[ii] Tartars, fat, felt, cheese, and milk were never involved. Yet despite evidence of the fictive nature of the original story, Beuys’s version still stands as a peculiarly sensitive and under-examined topic.

Mark Rosenthal has written perceptively on the mythical nature of Beuys’s work, concisely stating that “to understand Beuys’s approach and to characterize his aesthetic legacy, it is crucial to recognize that he approached both his life and his art as one endeavor, and constantly staged both aspects.”[iii] In other words, Beuys was an artist with a clear understanding of the power of myth, which he also recognized must be accepted as truth in order to achieve its full generative potential. In his fictive encounter with the Tartars, Beuys created for himself a story of rebirth and forgiveness which allowed him to leave the shame of his time as a decorated Nazi pilot behind him and re-emerge from the ruins of his broken body as a holy man for the 20th century, ready to heal the shattered psyche of Europe as he himself had been healed.[iv]

Acknowledging the consciously fictive aspect of Beuys’s production clearly alters the understanding of his oeuvre in important and productive ways. Yet doing so also undermines the artist’s intentions, effectively destroying an aspect of his work, and it is probably for this reason that his supporters are sometimes reticent to discuss the mythic underpinnings of his production or simply dismiss them as unimportant. Perhaps it is also for this reason that the discovery of his story’s fiction has not led to greater questioning of other aspects of his production.

Indeed, although the death of the artist represents a tragic loss of potential knowledge, the distance created by Beuys’s passing in 1986 has also aided in understanding his work. During most of his lifetime, even critics who remained unconvinced of his objects’ artistic or intellectual value seem to have taken the artist at his word as to their material content. Only now, a generation after his death, has the necessary historical distance formed to allow a re-evaluation of even the most fundamental points of the artist’s creations, including the very media in which he infused such profound symbolic significance.

The specific subject of this study is an untitled work often referred to as the “vitrine containing ‘Action Apron.’” It is one of four vitrines assembled in 1983 and purchased in 1991 by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York from the London-based Anthony d’Offay Gallery. Created to house remnants of his past performances, Beuys’s vitrines have their closest parallels in reliquaries and the display cases of traditional natural history museums. Thus, all of the objects within the case are both independent art works and components of a later, collective whole. When assembled, the remnants constitute a kind of self-portrait of the artist, a point reinforced by the metaphoric design of the case which Beuys claimed resembled the spindly legs and thick body of a stag, the animal with which he most related.[v] Given this element of self-portraiture and the fact that the artist clearly intended selected objects to be shown together, the vitrines should above all be understood as singular objects with multiple components rather than simply containers for the “real” sculpture.

The vitrine considered here contains remnants of four separate performances by the artist. According to the label supplied by Anthony d’Offay Gallery and probably written by the artist, these individual elements include: “Action Apron,” a white cotton apron worn during one of the artist’s actions in 1964; “Angel,” made from beef drippings with Irish unsalted butter and two coffee spoons in 1983; “Untitled,” a plastic tube containing what the artist claimed to be hare’s blood and color, from around 1977; and another “Untitled” work from 1966 consisting of a tin can containing thyme dipped in wax, a wax coated string, and blutwurst remnants.[vi]

However, according to analyses by Guggenheim conservators Carol Stringari and Nathan Otterson, “Angel” and the two untitled elements have questionable media which do not clearly match the descriptions given by the artist. The “beef drippings” supposedly present in “Angel” are not readily apparent, and, even more striking, the “Irish butter” appears instead to be a wax-based mixture with a small amount of butter mixed-in. Although the exact mixture is not identifiable without chemical testing, the relative absence of butter can usually be determined through observations of sight and smell. Not only would we expect butter to have softened and probably melted, deteriorating animal fat—such as that found in butter and beef—produces an unpleasant rancid odor. The fact that the whitish substance has preserved its shape and hardness while emitting only a mild buttery scent seems to indicate that the white block is neither mostly butter nor animal-fat. Similarly, although the artist presented his 1977 piece as consisting primarily of hare’s blood, the fluid and sediment now appear to be separated components of red ink. Finally, while the tin can does contain remnants of a thin, translucent substance along its inner wall which appears to be an organic product such as animal glue, there is little about this material that suggests the presence of blood sausage.

One rare precedent for questioning the artist’s materials comes from his widow, Eva Beuys. According to the contents of a 1998 e-mail in the Guggenheim’s files, Eva had doubts about whether blood existed in the tube, whether blood sausage could be found in the tin can, and whether there was any butter in the vitrine. Perhaps most importantly, the e-mail states that, according to Eva, no butter was originally present. This last point is crucial because it represents the only evidence I found that confirms it was the artist’s choice to use a substitute for butter rather than a decision made later by the gallery. Of course, it does not exclude the possibility that the label was a fiction created by the gallery. However, the specificity of the type of butter (“Irish unsalted”), as well as the fact that the artist was not only alive when the gallery first displayed the vitrine but that he actually composed the work for d’Offay’s exhibition, makes this latter scenario unlikely and strongly suggests that the labeling is the product of the artist.

In addition to the concerns raised by Eva Beuys, the Guggenheim conservators have found issues with objects in other vitrines from the same series that seem to reinforce the idea that Beuys substituted materials. Most suggestively, in the Sled with Filter vitrine (see above image), the “fat” in the “Fat Filter” component appears to be wax.[vii] Such irregularity in his production is consistent with the observation made by Stedelijk Museum conservator Kees Herman Aben that Beuys rarely gave accurate or specific descriptions of the type of fat he used.[viii] The artist himself stated casually that he just used “any sort of fat,” although he was fond of margarine, which he found to be particularly banal and therefore shocking.[ix] He was also known to use lard, butter, wax, stearin, paraffin, mutton fat, beef suet, pork fat, wool fat, and tallow, all of which seem to be included under his broad, loose category of “fat.”[x] If Beuys conceptualized these diverse substances as being essentially the same—and therefore interchangeable—then it is possible he truly saw no significant problem in using wax in place of butter when making “Angel,” even if the idea of a specific kind of butter was important for the piece.

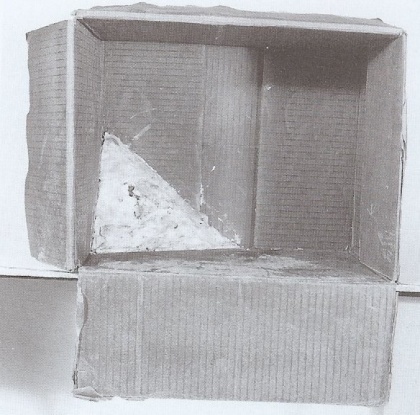

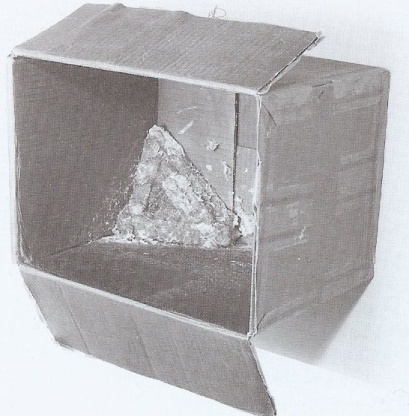

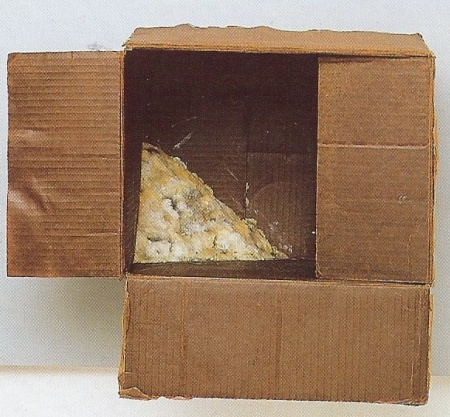

One of the reasons relatively little analysis has been done on Beuys’s materials is that, under normal museum storage conditions, they are fairly stable.[xi] However, when put on view, objects containing fat and wax can suffer from the heat produced by gallery lights. One such instance occurred at the Stedelijk Museum during the artist’s lifetime, in 1977. When faced with the deterioration of their work from 1963, Fat Corner in Cardboard Box (Fettecke in Kartonschachtel), the museum undertook a potentially controversial reconstruction of the object.

Although the piece had apparently been fine while in storage, it began to suffer once put on display. Exposure to heat, damp, micro-organisms, alkaloids and metals accelerate putrefaction of animal products, and in this case the heat created by the gallery lights caused the fat to melt.[xii] Not only did the corner lose its shape, but the cardboard and felt became dark and greasy.[xiii] When removed from its Plexiglas case, the work gave off the strong, rancid smell expected of deteriorating, fourteen year old fat. Without consulting the artist, the museum decided to reconstitute the piece using a mixture of 80% stearin, 17% linseed oil, and 3% beeswax.[xiv]

Aben, who wrote about the reconstruction in 1995, lamented the decision had been made without consulting the artist, who he suspected would have preferred to allow the object to deteriorate.[xv] However, if Beuys felt that the idea of the substance and what it signifies can be embodied in another, similar medium, then it seems probable that the artist would have accepted reconstructions of his objects to stand in for the originals. Indeed, if the Guggenheim conservators are correct, just a few years later the artist himself substituted a wax mixture in “Angel” for the more unstable substance of butter. Such action would suggest that, at least towards the end of his career, he would not have minded the Stedelijk Museum’s switch.

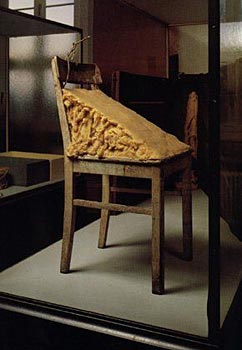

Yet the idea that media which act as differently as paraffin wax and butter are interchangeable seems troubling in the context of an artist for whom the behavior of materials was paramount. According to Beuys’s Theory of Sculpture, which the artist developed in the 1960s, everything passes through a continuum of structure which ranges from chaotic to ordered, with the ideal state resting between these two poles. The chaotic pole is associated with warmth, raw materials, and raw will, while the ordered, crystalline state is represented by cold, processed materials, and the intellect. As Caroline Tisdall has pointed out, fat can embody both extremes, from a warm and flowing raw material to a cold and ordered solid, a quality the artist famously exploited in works like Fett mit Stuhl (1964, below), in which the potential softness of the fat is juxtaposed against the geometrical right angle of the chair.[xvi] Again, though, “fat” is an incredibly broad category, and some types of fatty materials are naturally closer to one end of the Theory’s spectrum than the other. Beuys’s apparent choice, made twenty years after the development of his theory, to use a hard wax to represent butter may very well suggest an even further shift in the artist’s thinking away from literal referentiality towards near-complete metaphysicality.

Beuys’s interest in the transformation of materials extended to his process-oriented sculpture. As a result, it can be argued that his objects should be allowed to run their natural course, even to the point of deterioration. Indeed, long-time Beuys conservator Otto Hubacek recalled that Beuys would not repair damaged works, although in one instance he allowed a work to be exhibited that the then-young conservator had repaired for a museum (unknowingly against the artist’s wishes).

However, deterioration and flux are not necessarily the same, and there is nothing to suggest that Beuys actually wanted his sculpture to destroy itself over time. Instead, the artist’s behavior towards his objects suggests that he felt a piece was simply over once it was badly damaged. Supporting this interpretation of his feelings is the fact that Eva Beuys’s has come out strongly against deteriorated works being presented as functioning objects at all. Yet, in order to preserve the works for any length of time, the museum must keep them in their ordered state, which in Beuys’s continuum is analogous to death. On the other hand, the only way to activate the original fatty materials is to heat them, which would cause the physical death of the object.

One way to work around this apparent impasse between the temporary nature of the sculptures and the desire for longevity would be to treat the process-oriented works as both objects to be conserved and performances that could be re-performed. In this way, the original object could be traditionally preserved, but the idea behind it could be re-actualized through the creation of similar, temporary sculpture as exhibition copies. Intended only to be experienced, these performative pieces would not need to be kept and stored, but should be destroyed at the end of the exhibition for which they were created.

As catalogues of the artist’s previous actions, however, the vitrines are the most conceptually resistant to substitutions. Their aspect of self-portraiture—in fact, the basis of any meaning they might possess—is dependent on the components’ status as objects physically made or selected by Beuys at a specific time in his life. More clearly than his other works, they invite emphasis on temporal originality, preservation, and stasis. At the same time, part of the artist’s interest in grouping elements from disparate time periods might have been to juxtapose objects at differing states of deterioration, the physical status for which would be based on both their materials and ages. All of this suggests that in the case of the vitrines, even if the estate would allow it, substitutions should be avoided in all but the direst cases of deterioration, such as when the status of an object endangers the stability of the overall vitrine.

Ironically, while Beuys’s own material substitutions make his objects more stable, they also complicate, on a very practical level, the Museum’s ability to show the work. Before the Guggenheim can put the vitrine on view or make it available online, it must decide on how to present at least the basic tombstone information. Aside from the philosophical and ethical issues tied up in changing an artist’s label, part of the problem with altering the media line is that the precise materials of each component are still not clear. For instance, although the liquid in the 1977 tube is clearly separated ink, one would have to open the tube in order to determine with certainty whether or not any blood is also present, an action which would damage the piece. In addition, the original medium is written ambiguously enough (“hare’s blood with color”) that recognizing the liquid and sediment are mostly from ink still does not entirely disprove the artist’s assertion. Similarly, although no clear evidence exists for the presence of “beef drippings” supposedly in “Angel,” it seems possible that their lack of presence is due to the passage of the more than 25 years since they were supposedly dripped over the sculpture. Likewise, even if we believe that the whitish-yellow substance is mostly wax rather than butter or even lard, the exact mixture has yet to be determined. Therefore, although the contents may not be exactly as Beuys described them, we cannot formally change the authoritative tombstone information without having equally precise facts with which to replace it. Wall and object label text is a potential site for a slightly more elaborate explanation of the media, but this option is also problematic in that it would detract from the objects’ intentionally mythic aura and thereby further disrupt viewers’ understanding of the artist’s work.

At this point many important questions remain regarding the “Action Apron” vitrine and, by extension, the artist’s practice as a whole. Among the most pressing of these is the still unresolved issue of what materials were used in “Angel” and the “Untitled” tube. Given the current divergent interpretations of the objects’ materiality, the components of at least “Angel” need to be tested and their media definitively understood before conceptual analysis can move forward.

Even with these unanswered questions, I must disagree with the assertion frequently made by the conservators I interviewed that the exact composition of materials does not matter in preserving the intellectual content of the work. When an artist merges materiality with meaning as explicitly as Beuys has done, the question of how he chose to use his media directly affects our understanding of the artist and his practice. For conservation, the possibility that the artist staged his compositions with more stable compounds would seem to make reconstructions of degraded objects—like that undertaken by the Stedelijk Museum—more ethically feasible than if the artist was inflexibly tied to literal, rather than metaphysical, materiality. In addition, if museums were able to substitute “performative” works for display purposes, viewers would more likely be able to experience the pieces as Beuys intended.

The very fact that questions are being raised about Beuys’s media is new and potentially crucial in gaining a better understanding of his production. I suspect that further analysis of materials used throughout the artist’s oeuvre, and especially in his late work, will reveal an artist for whom conventional concerns with theatricality and sculptural longevity were more important than he chose to project. How museums and scholars choose to interpret this information and present it to the public remains to be seen.

Bibliography

Aben, Kees Herman. 1995. “Conservation of Modern Sculpture at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam,” in From Marble to Chocolate: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture. London: Archetype. 104–09.

Barker, Rachel and Alison Bracker. “Beuys is Dead: Long Live Beuys! Characterising Volition, Longevity, and Decision-Making in the Work of Joseph Beuys,” Tate Papers (Autumn 2005), unpaginated: www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/05autumn/barker.htm

Beuys, Joseph. 2004. “Joseph Beuys: Life Course/Work Course,” in Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments. Houston: Menil Collection. 159.

Buchloh, Benjamin H.D. “Beuys: The Twilight of the Idol,” Artforum, Vol. 5, No. 18 (January 1980), 35–43.

The Museum of Modern Art. 2008. “Focus: Joseph Beuys,” (gallery label text). Available online at: http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=118971<

Rainbird, Sean. 2004. “At the End of the Twentieth Century: Installing After the Act,” in Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments. Houston: Menil Collection. 136–49.

Rosenthal, Mark. 2004. “Joseph Beuys: Staging Sculpture,” in Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments. Houston: Menil Collection. 10–135.

Schmuckli, Claudia. 2004. “Chronology and Selected Exhibition History,” in Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments. Houston: Menil Collection. 150–201.

Spector, Nancy, Mark C. Taylor, Christian Scheidemann, and Nat Trotman. 2006. Barney/Beuys: All In the Present Must Be Transformed. New York: Guggenheim.

Theewen, Gerhard. 1993. Joseph Beuys: Die Vitrinen, ein Verzeichnis. Köln: Walther König.

Tisdall, Caroline. 1982. Joseph Beuys: dernier espace avec introspecteur, 1964–1982. London: Anthony d’Offay.

Tisdall, Caroline. 1979. “Fat Chair,” in Joseph Beuys. New York: Guggenheim. 72-76.

[i] Rosenthal, Mark, “Joseph Beuys: Staging Sculpture,” in Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments (Houston: Menil Collection, 2004), 10.

[iv] Rosenthal offers a similar interpretation of Beuys’s creation story. Ibed.

[v] MoMA, “Focus: Joseph Beuys,” (gallery label text, 2008). Available online at: http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=118971

[vi] Blutwurst is the German name for what in the United States is known as blood sausage and in England as black pudding.

[vii] I did not observe this piece in person.

[viii] Aben, Kees Herman, “Conservation of Modern Sculpture at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam,” in From Marble to Chocolate: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture (London: Archetype, 1995), 107.

[xi] All of the conservators I contacted store their objects in regular museum storage rather than refrigerated conditions. Lynda Zycherman explained that the MoMA had considered refrigeration for their organic objects, but decided that the tactic was too risky and untested for mixed media, as cold conditions can actually be detrimental to some materials.

[xvi] Tisdall, Caroline, “Fat Chair,” in Joseph Beuys (New York: Guggenheim, 1979), 72.