Of the many exceptional Maya ruins we visited in the Yucatán Peninsula, both Josh and I agree that Uxmal was our favorite. My notes from the half-day we spent at the site simply read “Uxmal=Amazing,” and that still pretty well sums up our impression of the ancient city.

Like Chichén Itzá, Uxmal is an UNESCO World Heritage site located within day-trip distance of Mérida. However, its more southwesterly position off a less trafficked route means that it is not as convenient a destination for cruise travelers or those staying in Tulum, and thus receives fewer visitors than its slightly more famous cousin. This is good news for those who do put in the small amount of extra effort necessary to get there, as it not only means you will be sharing the grounds with fewer people, but also that those other people usually care about what they’re seeing (a characteristic we didn’t fully appreciate until later, when we found it lacking among too many of the tourists populating the Maya Riviera).

When traveling within the peninsula, moving south generally means moving back in time. Whereas the buildings at Chichén Itzá mostly date to the Post-Classic era (c. 11th-13th centuries CE), Uxmal is a Late Classic site, built primarily between the 7th and 10th centuries CE. It is the largest and most complex of the cities designed in the Puuc style, and one of the few Yucatan centers not near a cenote. Instead, the residents dug chultuns (deep, narrow cisterns) to capture rain water. The many masks that typify the stone latticework in Puuc architecture have long been thought to represent Chaac (Chac, Chaahk), god of rain, in part because rain would have been both relatively scarce and extremely important to the city’s survival.

[Note: According to a display at the Canton Palace Museum, some recent studies have suggested that these masks might be depictions of Witz, the sacred mountain, rather than the rain deity. However, another plaque located a few feet away in the same exhibition clearly takes the more traditional view that these are the faces of Chaac. Since the question is still contested, I am using the traditional identification of the masks as Chaac because it is both the more widespread view and the one most repeated at the site itself.]

Although more difficult to capture in photographs, the layout of Uxmal is almost as striking as its highly decorated architecture. After visiting Chichén Itzá and Dzibilchaltún, where the major buildings are spread out and emphasized through man-made horizon lines, the relationships between buildings in Uxmal can feel layered and compact despite the substantial size of the site. This is particularly true of the area around the Magician’s Pyramid. Even though the structure is one of the largest and most conspicuous monuments in the ancient city, the courtyard (known as the “Quadrangle of the Birds”) separating it from the buildings of the “Nunnery” is quite small—so small, in fact, that it is impossible to capture the entire front of the pyramid in a single photograph. This means that there are few opportunities to view the face of the pyramid as a whole. And yet, the building’s upper portion is one of the most visible and eye-catching sights in the city, with a giant, open-mouthed mask looking out towards the Nunnery and marking the entrance of the temple located at the top of the central staircase. Instead of opening the space around the pyramid so it could be easily understood as a whole, the city’s builders created multiple opportunities for visually framing, and thus drawing specific attention to, this mask.

Case in point:

And so on.

And so on.

No other single feature stands out so dramatically at the site, especially when seen from a distance, suggesting that it was this part of the pyramid, rather than the totality of the structure, that held the most significance for the city’s residents. The doorway is also unusual for Puuc architecture, and appears to be a blend of local Puuc and southern Chenes decorative styles. For instance, the use of stacked Chaac masks (seen here at the edges of the central face) is a typically Puuc (and Chenes) feature, while Chenes architects frequently incorporated open-mouthed serpent masks around the doorways of important buildings. In fact, the closest known parallel may be at Hormiguero, one of the most far-flung of the Chenes-style sites, located nearly 300 km away in the south of the Peninsula.

Unfortunately, no one now knows exactly what Uxmal’s structures, including the Magician’s Pyramid, were used for. The city had long been abandoned by the time the Spanish arrived and christened the buildings with names based on their own initial impressions of the site. However, modern scholars have noted that Uxmal’s layout appears to follow astrological features, particularly the movements of the sun and Venus. The cycles of both celestial bodies played definitive roles in Maya conceptions of time, but how that translated into the uses of these buildings is still largely a matter of speculation.

The unfortunately named Nunnery, located near the site’s entrance beside the Magician’s Pyramid, is a slightly asymmetrical complex with long, heavily ornamented buildings framing a large courtyard. The light show, held in the evenings just after dusk, takes place here, with the audience sitting in folding chairs near the top of the northern building.

Most scholars believe that both the layout and decorative façades of the Nunnery possess dense symbolism. The buildings themselves may have formed a mandala of the Maya universe, with the tall, north building embodying the Upper World; the short, southern building representing the Underworld; and the east and west buildings standing for the rising and setting aspects of the Middle World (Coe 360). If correct, the complex—built toward the end of Uxmal’s peak—was a physical declaration of the city’s place at the center of the universe.

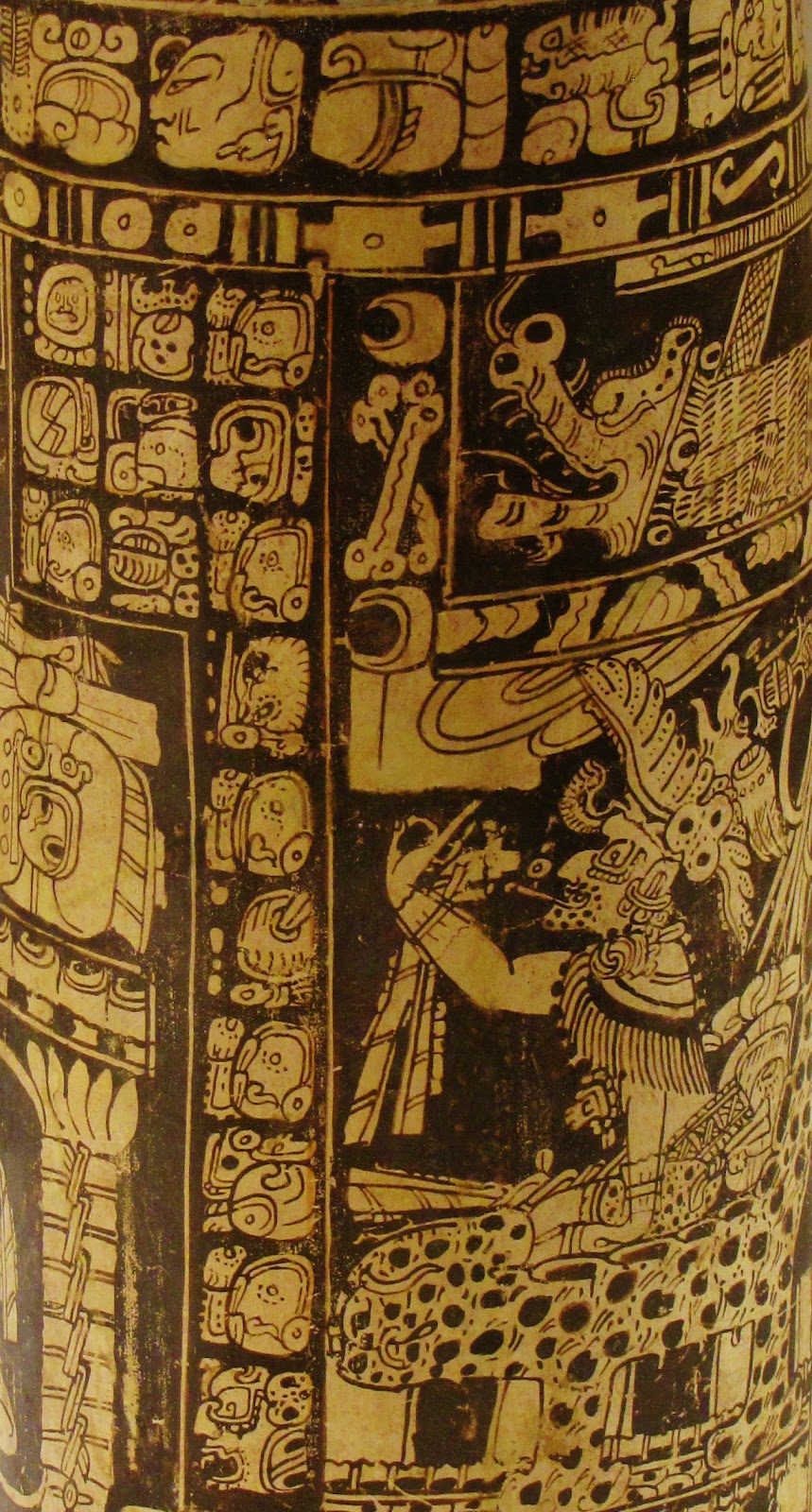

In addition to the ubiquitous Chaac masks, the courtyard-facing imagery includes repeated depictions of double-headed or feathered serpents, Maya huts, jaguars, and even masks of Tlaloc, the goggle-eyed water deity associated with central Mexican cultures. The cross-hatching designs, common throughout Uxmal, depict mats, emblems of power.

From the Nunnery, we walked through the small ballcourt, past the stepped hill supporting the Governor’s Palace, over the Dovecote, and up the Great Pyramid.

Unlike the Magician’s Pyramid, the Great Pyramid’s 100 feet of steps are still open to those visitors who are willing to climb them. Which we did.

In addition to offering a view of the city’s central buildings, the platform at the top of the pyramid supports a small temple decorated with macaws—perhaps representing an aspect of the sun god—and more long-snouted masks, some of which hold human heads in their mouths. Only one side of the pyramid has been reconstructed, and it is not possible to enter the temple proper.

The northeast corner of the Great Pyramid abuts the man-made hill that forms the platform for the Governor’s Palace (or House of the Governor) and House of the Turtles. Walking around the narrow south end of the Palace leads to an open plaza that faces the front (east) side of the building.

Near the center of the plaza, directly before the Palace’s staircase, stands an altar supporting Uxmal’s two-headed jaguar throne. Excavations revealed a large cache of over 900 objects, including pots, jade jewelry, and obsidian knives, buried beneath this altar (Coe 360). Although we were unaware of it at the time, Coe also notes that an invisible line corresponding “to an important point in the Venus-cycle” runs from the central doorway of the House of the Governor, through the throne, to the largest structure at the nearby site of Nohpat (361). This relationship between the two cities is further emphasized by the fact that they were once also directly connected by a sacbe (white road).

From the plaza, it becomes clear that the Palace is in fact three separate buildings connected by spear-point arches and unifying visual features, including one of the most intricate friezes of the region. Altogether, the buildings run for over 100 meters, making the three-part unit one of the longest palace-style structures of any Maya city. Visitors can walk up yet another platform to approach and look into these buildings, but are not supposed to enter them. The rooms currently hold unassigned architectural fragments and serve as cool-ish resting places for iguanas.

The northern corners of the Palace have been dug out to reveal more Chaac masks sunk below the walkway. Their strange placement may indicate that the patio area around the structure represents a later building stage than the rest of the House of the Governor.

Descending from the Palace, we approached the House of the Turtles, located at the northeast corner of the hill-platform.

Some scholars have proposed that the House of the Turtles, named for the row of 40-plus stone turtles encircling the upper portion of its roof, may have been dedicated to a rain “cult,” since turtles are associated with rain. If that is the case, however, it raises the questions of why no images of Chaac adorn the building, especially given the proliferation of the god elsewhere at the site (there are over 100 such masks on the Governor’s Palace alone), and why one of the only other depictions of turtles in the city is clearly attached to the god of the underworld (see image of God N relief at the Nunnery, above).

The relative austerity and small size of the building complements the ornate enormity of its neighbor. Its exterior is punctuated by 10 doors: three each on the east, west, and south walls and just one in the north. Another sight-line leads from the central doorway on the south wall, through the northern opening, across the ball court, to the central entrance of the Nunnery’s south building.

For our last stop, we walked west to the “Cemetery Complex,” which, in keeping with the misnomers that abound at the site, is not an actual cemetery. Named for the numerous images of skulls and cross-bones carved on the low platforms dotting its main square, the Complex includes a heavily overgrown pyramid and temple platform. Much of the western area has yet to be reconstructed and is thus far less spectacular than the eastern side of the site. Even so, this quiet group offers the rare opportunity for close inspection of in situ, fairly well preserved reliefs that make it another not-to-be missed section of an already remarkable place.

Highly subjective personal rating: 10/10

Bonus pics: