![Gonzaze Myō-ō, Nakabayashi Gennai, wood with polychromy, 1680 [Edo period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/2IMG_2233.jpg)

![Shūkongōjin, wood with traces of polychromy, 12th/14th century [probably Kamakura period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/10IMG_2227-cropped.jpg)

!["Running in Advance" Mask (Shinshōtoku), wood with traces of color, 15th/16th century [probably Muromachi period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/14IMG_2217.jpg)

![Fudō Myō-ō, wood with polychromy and gilt-bronze accessories, 12th/14th century [probably Kamakura period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/19IMG_2232.jpg)

![Demon Mask (Tsuina-men), wood with traces of color, 15th/16th century [probably Muromachi period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/21IMG_2209.jpg)

![Seitaka Dōji, wood with traces of polychromy, 15th century [Muromachi period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/26IMG_2198.jpg)

![Zenzai Dōji, wood with glass and polychromy and metal accessories, 12th/14th century [probably Kamakura period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/28IMG_2205cropped-1.jpg)

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz

vegetarian in a leather jacket

art, travel, culture

![Gonzaze Myō-ō, Nakabayashi Gennai, wood with polychromy, 1680 [Edo period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/2IMG_2233.jpg)

![Shūkongōjin, wood with traces of polychromy, 12th/14th century [probably Kamakura period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/10IMG_2227-cropped.jpg)

!["Running in Advance" Mask (Shinshōtoku), wood with traces of color, 15th/16th century [probably Muromachi period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/14IMG_2217.jpg)

![Fudō Myō-ō, wood with polychromy and gilt-bronze accessories, 12th/14th century [probably Kamakura period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/19IMG_2232.jpg)

![Demon Mask (Tsuina-men), wood with traces of color, 15th/16th century [probably Muromachi period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/21IMG_2209.jpg)

![Seitaka Dōji, wood with traces of polychromy, 15th century [Muromachi period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/26IMG_2198.jpg)

![Zenzai Dōji, wood with glass and polychromy and metal accessories, 12th/14th century [probably Kamakura period], Japan. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/28IMG_2205cropped-1.jpg)

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz

In Part 1 of this review, I focused on the contentious origins of the new Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and the problematic concept of provincialism that quietly plagues any small or medium-sized cultural center in this country.

Built with the purpose of redefining a predominantly rural community as a new cultural destination, the greatest challenge for the CBMAA is to create a space and collection capable of meeting the established standards for world-class museums while also representing solidarity with its specific location.

Although the work on the grounds and building has yet to be completed, the museum has already proven itself to be generally successful in striking this delicate balance. In some instances, however, its achievement comes hand-in-hand with a curatorial timidity that has kept the CBMAA from being as intellectually daring as it could be.

Be that as it may, there is much to celebrate in the new Crystal Bridges Museum. One of its most refreshing aspects is the self-evident intention of all involved to create an innovative space that responds to the natural and cultural environment of the institution’s surroundings without sacrificing the larger story of American art.

Both in- and outside of the building itself, the curving lines and sloping shapes of Moshe Safdie’s architectural design clearly draw on the forms of organic bodies, while the many walls of glass invite as much contemplation of the world outside as the art within.

Not only does his design harmonize well with its natural setting, but it is in easy dialogue with another nearby structure of architectural note: the glass and steel Mildred B. Cooper Memorial Chapel, designed by Fay Jones and Maurice Jennings and dedicated in 1988.

If museums are the secular cathedrals of modernity, then the parallel designs of these two spiritual houses seem particularly telling. Both museum and chapel were designed to allow the natural world to visually penetrate the interior and define the visitor’s experience of the space. Taken together, the buildings’ shared concern with transparency and the inclusion of the natural environment suggest the development of a noteworthy local trope in contemporary architecture and the potential for the cultivation of a related style.

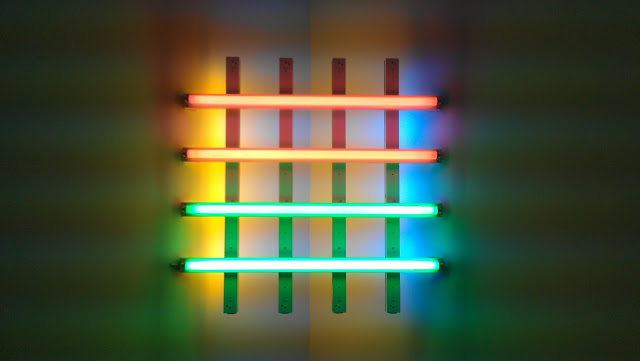

Similarly, landscape architect Scott Eccleston modified the CBM’s grounds, which constitute a lightly forested area with trails, streams, and—eventually—a lake that abuts the rear of the building, but did not drastically alter their character. The outdoor sculpture and installations, too, were chosen for their responsiveness to the natural environment, although the sensitivity or sophistication of this responsiveness varies. Highlights include James Turrell’s site-specific installation The Way of Color (2009), which incorporates native rock into his signature investigation of natural light effects; Roxy Paine’s stainless steel tree, Yield (2011), located at the museum’s entrance; and Mark di Suvero’s Lowell’s Ocean (2005–2008), visible both in- and outside of the building.

A preoccupation with nature continues throughout the collection, along with a few other areas of focus. The CBMAA’s own literature describes these themes as “artists’ encounters with and responses to nature; strong women, both as subjects and makers of art; the ongoing dialogue between American artists and other world cultures; and the continuing role of the artist as innovator.”

For a nature-loving, feminist, cross-cultural art historian like myself, that is a very exciting declaration of intent.

A wander around the museum revealed the list to have been arranged in decreasing order of success or urgency, although each concept was indeed present. A fifth motif, not mentioned in the literature but clearly woven throughout the collection, was the subject of conflict. However, this is perhaps the inevitable but unintended consequence of focusing on works that deal with issues of nature, gender, innovation, and cross-cultural interaction.

I was pleased with the quality and selection of much of the work on display throughout the collection, a sample of which can be found in the images at the end of this post. I also liked that between the chronologically divided sections were areas where people could sit and peruse any of a large collection of books. While tables supporting a few exhibition catalogues directly related to the show at hand have become commonplace in temporary exhibits, the selections provided by the CBM are far more comprehensive—and the sitting areas far more welcoming—than found elsewhere.

My greatest criticism of the museum is that it tends to be a little too safe, as was particularly evident in the temporary exhibition of contemporary work titled, Wonder World: Nature and Perception in Contemporary American Art. Excluded from the title but endemic to the works featured in Wonder World was a clear preference for contemporary artists drawing on historical modes of making. Each of these topics—nature, perception, and traditional practices in contemporary art—is a welcome basis for an exhibition, and there is quite a bit of good work in the show. Yet, when viewed together, the pieces felt a little one-note and lacking in radically innovative contributions.

Stagnation is particularly a problem for a museum that takes “artist as innovator” as one of its driving concepts. And with a subject as broad as wonder, nature, and perception, the narrowness of artistic approach seems doubly strange. For instance, why not include people who take the systems of nature as their starting point? Or who play with the nature of nature via an investigation of physics or biology or even taxonomy? While there is nothing wrong with utilizing the convention of representation in contemporary art, there are so many contemporary artists working in non-representational modes, or whose relationships to nature and perception are both subtle and complex, that to lean so heavily on visually and conceptually straightforward works does a disservice to the exhibition’s topic and its visitors.

My other point of concern lies in the apparent definition of American art, which tends towards the mainstream or canonical (albeit expanded for both gender and, in the more recent sections, race). For example, although the collection includes depictions of Native Americans, I do not recall any historical objects by Native Americans in the main galleries.* I suspect this is due partly to lines drawn by citizenship and partly to pre-existing art historical categories put in place to make collections and the narratives they tell manageable and coherent.

In other words, the presence of these somewhat arbitrary collection standards and definitions is not only understandable, but in accordance with typical museum practice. However, should the CBM choose to complicate the concept of “American” in the future by incorporating works which do not stem mainly from European traditions, the story they could tell would be fuller and, in my opinion, more interesting. Such a shift would also represent a challenging and innovative curatorial decision that is already overdue in most museological practice.

Finally, the café is worth mentioning, as it represents a fusion of a high-end sensibility that is typical of museum eateries and the low prices that are a hallmark of both Wal-Mart and Midwestern towns. Even here, the museum exhibits a savvy awareness of the expectations of its varied audience that, if continued, will be the institution’s greatest strength.

Indeed, perhaps what the Crystal Bridges Museum does best, and what it needs to do most, is break down the centuries-long fallacy that nature and culture represent binary opposites. During a period of wide-spread concern for the environment, increased use of urban gardens and suburban farms, and the decentralization of ideas and information away from large cosmopolitan cities, a new museum that takes the fusion of nature and culture as its basis is truly an institution that embodies the concerns of its time.

For further exhibition and visiting information, go to the Crystal Bridges Museum website: http://crystalbridges.org/.

*The CBM does have a dedicated section of cases that presents samples from the collections of other local museums. In addition to representing a uniquely neighborly practice, the cases also suggest the kinds of materials that may be related to, but are not otherwise present in, the CBM’s own collection. Among these is a display for the Museum of Native American History (formerly the Museum of Native American Artifacts).

![John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Theodore Atkinson Jr. (Frances Deering Wentworth) [detail], 1765. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://images-blogger-opensocial.googleusercontent.com/gadgets/proxy?url=http%3A%2F%2F1.bp.blogspot.com%2F-FsvCiIY0_3Q%2FTxfvuuaPNSI%2FAAAAAAAAAQo%2FniccNbOc5kQ%2Fs640%2FIMG_1724.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

![John Singer Sargent, Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife [detail], 1885. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://images-blogger-opensocial.googleusercontent.com/gadgets/proxy?url=http%3A%2F%2F3.bp.blogspot.com%2F-35n7Dv-oCLg%2FTxf0kjx7L0I%2FAAAAAAAAASA%2FPDM8j3ALSlQ%2Fs640%2FIMG_1814.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz

Back in 2005, Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton reportedly purchased Asher B. Durand’s 1849 painting, Kindred Spirits, for $35 million. While the practice of incredibly wealthy people paying incredibly high prices for paintings would normally receive little more than a shrug or eye roll by most jaded capitalists, Ms. Walton’s case drew a bit more attention because to acquire the painting she outbid a joint attempt by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art to purchase it. Doing so also served as a national public announcement of her intention to build a new museum of American art in her hometown of Bentonville in northwest Arkansas.Although the deal warranted coverage in the New York Times, I only learned of the semi-scandalous venture a few years later via my husband’s grandparents during a visit to their home in Bella Vista, a small suburban town neighboring Bentonville. Good hosts and frequent champions of the Waltons, they relayed the tale both with the intention of entertaining us as well as a sincere pride in the impressiveness of Ms. Walton’s victory over such major institutions.

My own reaction was more ambivalent.

I sympathized with the desire to create a public institution that served a community which otherwise did not have much in-person access to major works of art. I also believe that there is something to be said for spreading culturally significant objects around to different locations (as a security measure against disaster, at least). And although all museums want to build the strongest and most cohesive collections possible, it is difficult to argue that the Met or National Gallery “need” another painting. Indeed, although much can be said about the historical significance of Kindred Spirits, the overall collections of museums like the Met are so vast that even major works of art can be easily overlooked by the casual visitor. If you want to highlight the importance of an individual piece, smaller venues tend to be best.

On the other hand, when it comes down to the numbers, it is impossible to suppose that as many people will see objects housed in a small town in Northwest Arkansas as would in either New York or Washington DC.

Ethically, too, the purchase rankled. Although everyone in the field knows that the art economy and its related institutions are dependent on the generosity of a handful of wealthy patrons, it is nonetheless unsettling to have a single individual tank the combined efforts of two large and distinguished cultural institutions. The fact that this money came from the Wal-Mart empire, one of the most divisive and problematic businesses of recent decades, only shone a brighter light on the morally ambiguous nature of the discipline.

Furthermore, it was—and is—difficult to read Ms. Walton’s purchase as occurring outside of this country’s supposed “culture wars,” in which progressiveness, urbanity, and both coasts seem to be grouped together and set against conservatism, ruralism, and the rest of the country. Although I grew up in St. Louis, I have spent most of my adult life in coastal cities or abroad. There are reasons for this that go beyond the simple necessities of education and employment, and yet I am still attached enough to my hometown to refer to my visits there as “going home.” At the time of our trip to Bella Vista, we had recently moved to New York so that I could pursue my PhD at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, and my ambivalence about Ms. Walton’s purchase and intentions for a museum were really only the other side of my already existing discomfort about my new place of residence.

New York is, after all, an undisputed center for art and culture in the United States. In terms of resources and historical importance, there is no better place to study art, especially the development of modern and contemporary art, in this country.

However, there were two things that I noticed early on that never stopped bothering me during my time in NYC. The first was an unshakable sense that the city had reached a point in which the creative forces that had made it great were being strangled by its own history. Work in galleries tended to be more safe than interesting. The differences between these and the “provincial” galleries of other cities were primarily twofold: 1) the New York galleries had a higher asking price for their objects and 2) even works from other parts of the globe were in easy dialogue with the New York-based movements of the mid-20th century.

The second trend I noticed is closely related to the first: the frequent recurrence of the term “provincial” (especially in academic settings) as a shorthand means of dismissing an idea, argument, place, work, or person. Beyond being obviously condescending and shabby scholarship, such use of the term is particularly absurd in a place like New York which is not only infamously obsessed with itself to the exclusion of most other places, but which had the same term frequently thrown at it less than a century ago when the entirety of the United States was understood to represent the cultural backwater of Europe. Of course, it is probably this very history that has fostered the current enthusiasm for applying the term elsewhere.

As a native of “fly over country”—and as someone who has seen places like St. Louis grow into increasingly complex but perpetually undervalued cultural centers—I am admittedly sensitive to these little jabs from my colleagues and peers. But there are advantages to being made aware of one’s own otherness, and in this case it has caused me to seriously question the very nature of provincialism in the 21st century.

After all, the idea of provincialism is based on a socio-cultural model in which ideas and goods converged and circulated primarily through a handful of urban centers (usually political or economic capitals), leaving everywhere else relatively isolated and therefore culturally inbred.

But the advent of the Internet, not to mention the increased ease of travel, has made this model nearly obsolete as it applies to smaller urban centers. Not that Internet access or travel guarantees increased creativity or a more cosmopolitan outlook. Certainly anyone wanting to deepen her own ignorance can do that as well as someone hoping to broaden her horizons. What the Internet does is decentralize information, making one’s knowledge-set an individual choice rather than an environmental inevitability.

Of course, this is only true for those who actually have access to the Internet. Poverty or lack of infrastructure—a serious issue in many rural districts—still prevent too many people from taking part in an increasingly global culture. Even these cases, however, represent a changeable and changing situation that differentiates them from the classic model of provincialism.

For those of us fortunate enough to participate in the global stream of ideas, the world is wide open. Indeed, as countless authors have already noted, the greater problem now seems to be in knowing what to pay attention to and what to believe. One of the results of this new circumstance is that the role of major cultural institutions, including colleges and museums, has become to narrow and direct our focus rather than broaden our horizons.

I believe it is that embattled privilege—the privilege of determining the narrative of culture—that has produced a certain intellectual rigidness in some of our finest academic institutions and lies at the heart of our so-called “culture wars.”

This is the context into which the Crystal Bridges Museum has been conceived and brought to life. Stay tuned for the second part of my review, which will deal with the museum itself.

Collection-based shows are always problematic because, to an even greater extent than in other exhibitions, the story they tell is limited and skewed by the parameters of a single institution’s holdings. However, every exhibition narrative is necessarily biased, and the particular kind of limitation intrinsic to the collection show is at least upfront and obvious.

In some instances, these limits can in fact create a useful lens through which to disrupt more familiar stories of an idea or time period. In the case of The Language of Less: Then and Now, currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the all-too-pat historical understanding of “Minimalism” as a masculine, New York-based movement is troubled by the exhibition’s more global and gender-balanced approach.At the same time, both the objects on display and the labels or wall texts accompanying them provide a clear introduction to the ideas behind the push towards simplified forms in the 1960s and beyond that is still broadly referred to as Minimalism. The exhibition (which is split into larger and smaller halves of historical and recent art) therefore offers fertile ground for the thoughts of those already familiar with the history of contemporary art as well as anyone looking for a means of developing an appreciation of Minimalist objects.

Smithson―who is perhaps still best remembered for his earthwork project in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, Spiral Jetty (1970)―is featured prominently in the exhibit with two rarely seen works, Mirror Stratum (above) and an untitled aluminum wall sculpture from the Stenn Family collection. Both pieces exemplify the artist’s interest in the repeated forms which comprise the basis of both natural structures and ancient architecture.

Mirror Stratum, a corner piece consisting of a series of square mirrors stacked in order of decreasing size, is particularly evocative of both the Mayan pyramids and crystalline formations that frequently loomed large in Smithson’s thinking and production. As such, the work exemplifies a kind of Minimalist production based on simple arrangements of repeated, industrially produced objects that manage to poetically suggest a far-reaching range of subject matter.In addition, just as Flavin’s light sculptures (above) command not only the space physically occupied by fluorescent tubing but all of the area filled by their light, Smithson’s stacked mirrors produce a reflected pattern on the wall that extends far above the objects themselves. While this is consistent with a common Minimalist concern with an object’s ability to activate and define the space around it, the effect is also specifically related to what the wall text describes as Smithson’s interest in mirrors as a material that was both “physically present and immaterial, a quality that puts the viewer on heightened alert.”

![Foreground: Alan Sonfist (American, b. 1946), Earth Monument to Chicago, 1965–77 [core samples from beneath the city of Chicago ordered according to color and material]. Background, center: Charlotte Posenenske (German, 1930–85), Series DW Vierkantrohre (Square Tubes), 1967. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/3IMAG0978-1.jpg)

Walther’s fishing net shares the grid aesthetic of classic Minimalism. However, as a found and interactive object dependent on its placement within a gallery space for its status as art, it also possesses a heightened gestural quality that clearly bridges Conceptualism.

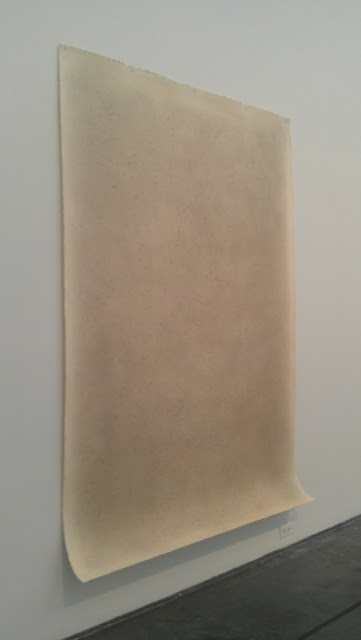

Tuttle also sought an open quality that is lacking in the contemporary production of many of his compatriots working within the Minimalist paradigm. Here, his dyed canvas lacks a clear top or bottom (and front or back) and can be installed anywhere in a room.

One commonality shared by many Minimalist artists is a concern with systems, often represented by the repeated forms of the grid. As noted by the exhibition’s curators, Stuart maintains this interest in “vast systems,” but turns instead to concrete models present in nature rather than the rigid, abstracted form of the grid. The complex, varied surface of Turtle Pond is actually a rubbing of soil, yet it suggests any number of subjects, from the pond of its title to the expanse of the universe.

Although To Underline was made in 1989, its origins lie in the 1960s when Buren began making paintings on striped awning. The found structure imposed by the pre-made stripes (a technique initially explored in the late 1950s by Frank Stella in his Black Paintings) helped to create a unity between individual paintings while drawing attention to the dimensions of each canvas.

![Foreground: Richard Serra (American, b. 1939), Prop, 1968 [lead antimony]. Background: Bruce Nauman (American, b. 1941), Untitled, 1965 [fiberglass and polyester resin]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/9IMAG1008.jpg)

![Carol Bove (American, b. Switzerland, 1971), Polka Dots, 2011 [bronze, steel, concrete, and shells] in front of Harlequin, 2011 [Plexiglas and expanded sheet metal]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG0901.jpg)

![Carol Bove (American, b. Switzerland, 1971), Untitled, 2011 [peacock feathers on linen]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG0895.jpg)

![Oscar Tuazon (American, b. 1975; lives and works in France), I gave my name to it, 2010 [steel plate and fluorescent lamps]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG0918.jpg)

Additionally, The Language of Less compliments the content of the monographic exhibitions currently on view in the museum’s other galleries, including the smaller “MCA DNA” shows dedicated to Gordon Matta-Clark and Dieter Roth, both of whose works from the 1970s are indebted to ideas which had started to percolate the decade before.The introduction to Minimalism outlined in The Language of Less provides a particularly helpful background for the exhibit dedicated to Canada’s Iain Baxter& (b. Iain Baxter, United Kingdom, 1936), whose often humorous objects and installations are clearly rooted in the movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, many of his works poke fun at the production of his contemporaries or recent predecessors, and so make little sense without a background in other artists of that period.

![IT (collaborative name of Baxter, Elaine Hieber, and John Friel), Extended Noland, 1966 [velvet ribbon on fabric]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG1032-1.jpg)

![IT, Pneumatic Judd, 1965 [inflated vinyl]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG1033.jpg)

![Iain Baxter&, Television Works, 1999–2006 [Acrylic paint on reclaimed televisions; reclaimed pedestals and reclaimed metal wall brackets]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG1028-1.jpg)

Go to http://mcachicago.org/exhibitions/now for a list of the MCA’s current exhibitions and links to their descriptions.

Despite ample historical evidence to the contrary, the cliché that art and science necessarily represent contradictory or even opposite approaches to the world continues to thrive. The survival of this fallacious perception is most puzzling because contemporary art, more than any previous moment or movement, persistently reveals a close, if complex, relationship between the two broad disciplines. Indeed, one of the significant shifts between modern and contemporary art has been the increased tendency for artists to integrate the methods of science—such as research, interviews, and experiment—into their productions, albeit with a continued preoccupation with the experiential. This change is in part due to the ever-increasing availability and use of intrinsically documentary media, such as photography and film, as well as a social shift towards personal documentation and data-gathering tied to social media networks, concern over governmental surveillance, and portable devices that offer a variety of ways to collect and track personal information. The extent of this shift is exemplified in three current contemporary art exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago: Exposure, Talo/House, and Lunar.

Exposure: Matt Keegan, Katie Paterson, and Heather Rasmussen (on view through March 4, 2012) is the fourth installment of a series of exhibitions hosted by the AIC’s Department of Photography. Although problematically structured around the idea of exploring “diverse approaches to photography,” each featured photographer successfully delivers a coherent and intriguing body of work that raises an array of questions.[i] Given the nature of photography, it is not surprising that many of these issues revolve around concepts of documentation. For instance, although Heather Rasmussen initially seems to present Minimalist images of randomly distributed blocks of color, her series of photographs in fact records model reconstructions of catastrophic freight accidents, which she hand-makes out of cardstock and arranges to resemble found journalistic images from the web. What at first engages the viewer through abstract design slowly reveals itself to be a complex reference to the impact of modern standardization practices in shipping on industry and economics, of which large-scale and far-reaching disasters are a significant unintended consequence. Meanwhile, on two other sides of the room, Matt Keegan’s multi-part installation utilizes several forms of reference, documentation, and presentation—such as artist’s books presenting historical photographs of New York with brief texts related to Chicago’s contemporaneous industrial and social development—to evoke relationships between the two cities. Keegan’s strategic use of juxtaposition directs the viewer without dictating any conclusions, and thereby encourages both intuitive and logical engagement. Clearly, both Keegan and Rasmussen freely borrow from or make reference to strategies of production and evidence-gathering derived from scientific fields. However, neither do so as concisely as Katie Paterson.

In capturing mute expansions of nothingness, Paterson’s slides and photographs of black, empty space are reminiscent of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s visions of the sea and theater, while her meticulous labeling and concern with the mundane suggest the rigorous documentation strategies of performance and conceptual artists like Tehching Hsieh. Yet the interest of her work, History of Darkness (ongoing), does not lie in its relationship to its artistic predecessors, but rather in her adoption of scientific documentation and subsequent disruption of the intended consequences of such documentation. Taken in Hawaii with the aid of “one of the most powerful telescopes in the world,” the images capture points in space that are completely devoid of “celestial illumination.”[ii] Although essentially identical in appearance, they each represent different locations in both space and time, and are labeled according to their distance from earth in light years. In highlighting the negative space of outer space, Paterson draws attention to areas that not only typically go undocumented, but which, as photographs, represent an apparent paradox. By recording literal nothingness, these photographs become information about a lack of information, reversing the very purpose of such documentation and the expensive tools used to produce it. As an additional touch, Paterson continues the light humor of her project and its preoccupation with the untenable by numbering her prints as editions of infinity, a move which similarly makes the numbering of editions meaningless (in the conventional sense of establishing value based on scarcity) while neatly tying back to the underlying concept of the series.

Visitors exiting Exposure can step directly across a narrow hallway to enter the exhibition space of Talo/House (2002; on view until November 27, 2011), a three-channel, semi-immersive video installation by Finnish artist Eija-Liisa Ahtila. As the portrayal of a woman whose concept of time and space is collapsing due to her perceptual inability to filter, place, and logically organize sounds, House represents an updated, more sympathetic, continuation of Surrealism. Like the early 20th century movement, Ahtila is concerned here with the portrayal and experience of people diagnosed with psychotic disorders, and similarly attempts to recreate the sensations associated with these alternative states for her audience. Also like the primarily male members of the earlier group, she has chosen to relate this experience through the eyes of a woman. However, far from the mental freedom Surrealists associated with such conditions, Ahtila portrays her subject as increasingly isolated. Over the course of the film, the character tries to block-out the outside world from her home and head as a means of gaining some sense of quiet sanity.

More important for the topic at hand is the way in which the artist gathered her material. While the Surrealists were intrigued with the ideas of Freud and tended to form romantic relationships with women who operated as their muses (some of whom later spent time in mental institutions), Ahtila composed her story based on research and interviews. Although more clinical than her predecessors, Ahtila’s method and subsequent product is perhaps more sympathetic and grounded in reality, resulting in work that seems to give her subjects a voice beyond that of mere muses.

Viewers who also had the opportunity to see the 2008 exhibition, Arctic Hysteria: New Art from Finland, at PS1 in New York will be reminded of the contemporaneous videos by Ahtila’s compatriot, Veli Granö, whose work in that show consisted of the recreation of scenes or moments described as real by his subjects, but are more likely understood as signs of mental illness or delusion by the general public. Perhaps to an even greater degree than House, Granö’s productions suggest sympathy with his socially alienated subjects by withholding critical comment and allowing them a neutral space in which to relate their singular visions of the world. Ironically, the neutrality also suggests a similar level of clinical detachment, suggesting—as a scientist would—that it is only through such disinterestedness that the subjects’ experience may be fairly expressed and understood.

Finally, the multi-media, sculptural installation, Lunar (2011), by Spencer Finch represents yet another attempt to merge aspects of science with art. However, in this case the final product tends to both mine and mimic technology and design rooted in the forward-thinking sciences of the 20th century. As a kind of earth-bound lunar module, the sculpture utilizes solar-power to reproduce the moon’s luminosity, which the artist has measured using a colorimeter. At night, the collected energy shines as light from a large buckyball, a form that automatically references environmental experiments in geodesic domes, as well as the shape’s visionary namesake: Buckminster Fuller. Although visually engaging, Lunar is ultimately less rigorous and satisfying than works like House or History of Darkness, because its engagement with science is more cosmetic than conceptual and its apparent goals—to create a different way of depicting moonlight and suggest a fanciful narrative of a space module landing on the museum—is more novel than probing. Nonetheless, the very idea that simple references to the “hard” sciences can spark the imagination of viewers and therefore enhance an artist’s work is itself an indication that scientific thinking and its markers are not only acceptable within contemporary art, but are actively sought by current artists.

Lunar will remain on the Bluhm Family Terrace until April 8, 2012.

Additional readings and useful links:

Exposure: Matt Keegan, Katie Paterson, and Heather Rasmussen

http://www.artic.edu/aic/exhibitions/exhibition/exposure4

Katie Paterson

http://www.katiepaterson.org/

Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Talo/House

http://www.artic.edu/aic/exhibitions/exhibition/EijaLiisaAhtila

Veli Granö

http://www.veligrano.info/

Arctic Hysteria

Exhibition website: http://www.momaps1.org/exhibitions/view/164

Catalogue: Framework: The Finnish Art Review (Artic Hysteria Special Issue), No. 9 (June 2008) [ISSN 1459-6288]

Lunar by Spencer Finch

http://www.artic.edu/aic/exhibitions/exhibition/lunar

______________________________________

[i] http://www.artic.edu/aic/exhibitions/exhibition/exposure4

[ii] Exhibition wall text.

The related article on the relationship between Surrealism and the Naturhistorisches Museum, “The Art of Displaying Life and Death,” was published in the Spring 2010 edition of Anamesa.

All images under copyright of the author. No reproduction without permission (please).