Photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz and Joshua Albers, August 9, 2014.

Tag: Renee Mertz

Holy Cross Abbey, County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland

From Cashel we took a slight detour north in order to visit the late Gothic church of Holy Cross Abbey, located near Thurles in County Tipperary. Named for its relic of the True Cross, the abbey was restored in the late 20th century and is once again in use as place of worship and pilgrimage after spending centuries in ruin.

Holy Cross was initially founded in 1168 or 1169 by Donal Mor O’Brien for the Benedictines. However, O’Brien transferred ownership to the Cistercians in 1180, and the abbey remained in their care until its eventual suppression. The current structure was built in the 15th century and contains a number of fine Gothic details, including sculpted pillars and remnants of a frescoed hunting scene. Although much of the sculptural decoration displays an unusual degree of refinement, the abbey’s most charming and surprising features are the numerous symbols subtly carved into the interior’s stone walls like labor-intensive doodles.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 29, 2013, unless otherwise indicated.

Ennis friary and cemetery, County Clare, Republic of Ireland

The earliest remains of the Franciscan friary at Ennis (Inis) date to the late 13th century, although much of the building actually comes from the second half of the 15th century. Founded around 1285 under the royal patronage of the O’Briens, Lords of Thomond, the friary soon became a burial site for kings and earls, and the town of Ennis grew up around it. By 1617, only one friar remained.

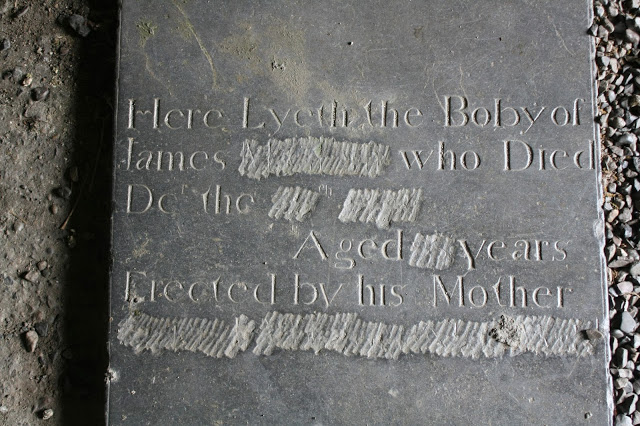

The site was undergoing a major reconstruction project while we were there, and relatively little of the decoration was in situ. Even so, Ennis possesses a number of fine examples of Irish Renaissance relief sculpture in its interior and decorated gravestones in its cemetery.

Ross Errilly Friary, County Galway, Republic of Ireland

Ross Errilly Friary is probably the best preserved Franciscan monastery in Ireland; it is also one of the largest. Yet the site is curiously absent from many guidebooks and harder to find than more tourist-ready destinations. As a result, we found it gloriously uncrowded.

Founded in 1351, the monastery was enlarged in 1498 and ultimately abandoned in 1753. Now left largely unguarded, the remains sit beside a slim stream amongst sprawling cattle pastures.

The central cloister demarcates the boundaries of the more private spaces of the monks’ former living quarters from the church and bell tower. The domestic sections include a bakery, kitchen (complete with a water tank for live fish), dining hall, and, on the upper floors, dormitories. The presence of more recent graves throughout the building suggests that the entire structure is still on consecrated ground.

Photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2013, unless otherwise stated.

Sligo Friary, Sligo, County Sligo, Republic of Ireland

Back in the Republic of Ireland, we decided to call it a day and spend the night in the port town of Sligo (Sligeach), which Wikipedia tells me is the most populous area of Sligo County. It is also the setting for Sebastian Barry’s bleak but beautiful novel, The Secret Scripture, which relates the history of 20th century Ireland through the life of a nearly 100-year-old mental patient.

Despite Barry’s less-than-complimentary depiction of Sligo as a town defined by its harsh weather, closed minds, and divided politics, we found the people friendly and the city center, perched along the River Garavogue, lovely. It was also surprisingly popular, and we had to try several B&Bs before we could find one with a free room.

Most places were closed by the time we settled-in on Saturday evening, so we decided to wait for the friary to open before leaving in the morning. As a result, we were the first people there and had the site almost entirely to ourselves for the duration of our visit.

Although popularly known as Sligo Abbey, the monastic ruins near the town’s center are technically the remnants of a Dominican friary. The terminological slippage is quite common—most “abbeys” in Ireland are in fact friaries—and quite understandable, as the two types of structures are nearly interchangeable in both function and appearance. The most basic difference is simply that monks (and abbots) lived in abbeys, whereas friars lived in friaries. Because a monk’s lifestyle was generally private—focused on personal prayer and meditation—abbeys tended to be closed to the broader public. Friars, on the other hand, went on preaching pilgrimages and encouraged their communities to worship in their churches. Architecturally speaking, the differences are even more subtle. Friaries usually have tall, narrow bell towers, while an abbey’s tower is relatively short and broad.

Sligo’s friary was founded in c. 1253 by Maurice Fitzgerald when the town was still a Norman settlement. Some of this early building survives, although much of the friary was rebuilt in the 15th century. Its most unusual aspects include a 15th century rood screen, two elaborate tomb monuments, and the only remaining sculpted stone altar in Ireland.

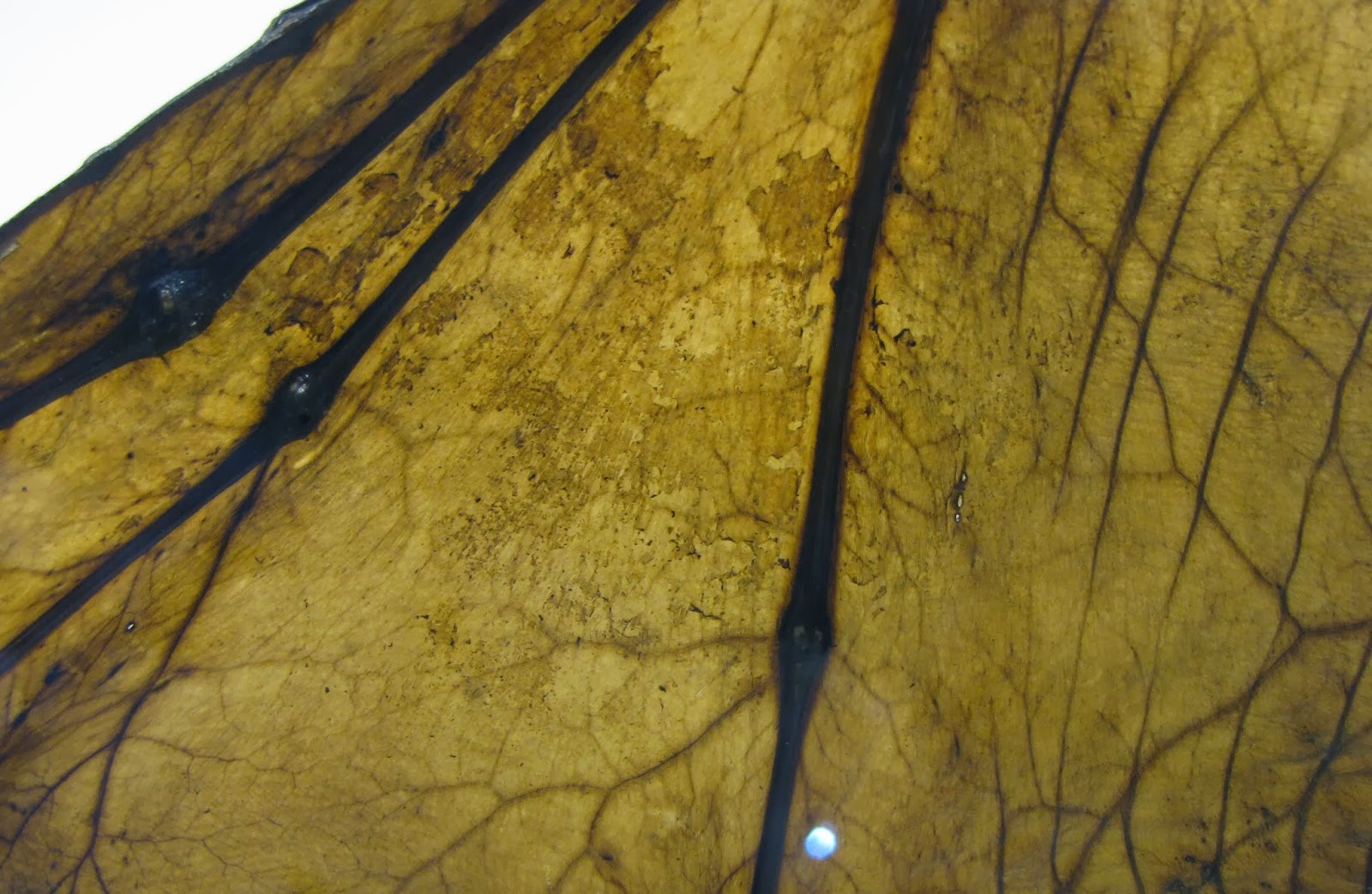

Although the altar is probably the most significant feature of the site, we were even more taken with the local Gastropods, particularly the large and rather weathered specimen we still affectionately refer to as “the Sligo Snail.” Perhaps the most expressive invertebrate I’ve met, we watched him/her devour flowers for at least a quarter of an hour. If you’ve never seen a snail eat, I recommend checking-out Josh’s time-lapse of the process. It’s kind of adorable.

Unless otherwise stated, all photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2013.