Throughout the long modern period, from the Renaissance to Jasper Johns, the visual arts have perpetually defined themselves against each other, even while endeavoring to simultaneously transgress their self-imposed boundaries. The advent of photography in the 19th century brought new urgency to these conceptual games, when for the first time painting, long held as art’s regent medium, had to prove its worth against a new technology that threatened to replace it. Of course, rather than rendering painting obsolete, photography ultimately freed the older medium from an obsession with mimesis and helped to usher in the styles of modernity that have come to define art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Impressionism, Expressionism, and even Cubism.

Now, the advent of digital arts—that newest of new media—has created a fresh challenge to more traditional materials. In its seeming immateriality, digital art possesses a fluid, transmittable bodylessness that is not only of the present (and future) moment, but that promises to be an accessible and democratic art form capable of circumventing the current insanity and inherent classism of the art market. As a result, the question facing contemporary painters and sculptors is no longer, “Why does my particular media matter?” but rather, “Why does art in any traditional media matter?”

The current Great Rivers Biennial at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis faces this challenge head-on by featuring three St. Louis-based artists who are deeply invested in materiality. They are, in fact, most clearly linked by their shared and unapologetic determination that matter matters. And each, in her or his own way, makes a strong case for the continued singularity of experiencing the physicality of objects.

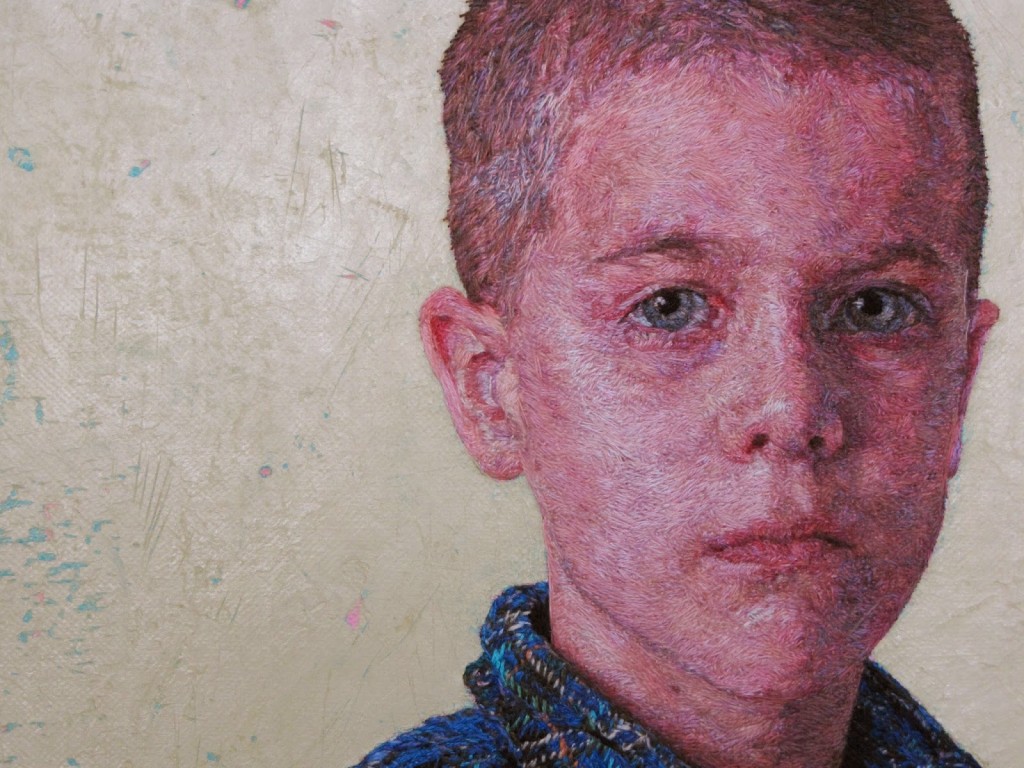

Cayce Zavaglia, Recto/Verso

In the aptly titled Recto/Verso, Cayce Zavaglia presents a series of embroidered portraits of friends and family alongside large-scale paintings depicting the backs of these textiles. While the embroidered pictures exquisitely and affectionately render their subjects in detailed, delicate realism, the paintings physically and psychologically dominate the gallery with their frenetic, abstracted surfaces. Although the paintings are in fact one step further removed from the people who inspired the original images, they seem to offer a more incisive and complex reading of their human subjects.

In both media, Zavaglia’s works also deal with a second, more subtle theme: that of the relationship between embroidery and painting. While the paintings are clearly based on her textiles, the textiles are equally indebted to the appearance of paintings. Portraiture is traditionally under the purview of painting, and Zavaglia has played with this expectation in her embroidery by creating stitching that closely resembles the marks of a paint brush. The textiles and paintings therefore resonate against each other through both their shared subjects and the interrelatedness of their media.

Carlie Trosclair, Exfoliation

For Exfoliation, Carlie Trosclair filled CAMStL’s central gallery with an open structure of flayed walls. Ragged-edged gaps in drywall frame vintage wallpapers and salvaged beams like an open wound pulled back to reveal another, even more damaged layer of skin hiding beneath the bone. Completing the immersive installation, Trosclair partially wallpapered the opposite wall and then proceeded to redefine the paper’s repeating pattern by carefully excising portions of the design, removing some areas completely and allowing others to curl towards the floor like mossy tendrils. Her unbuilt-constructions, broadly reminiscent of both geological fissures and abandoned hotels, play with notions of interior and exterior, nature and architecture, creation and decay, permanence and impermanence. And although her work is an almost pure meditation on materiality, it also circumvents the marketplace by being explicitly temporary, without a life (as art) after the show ends.

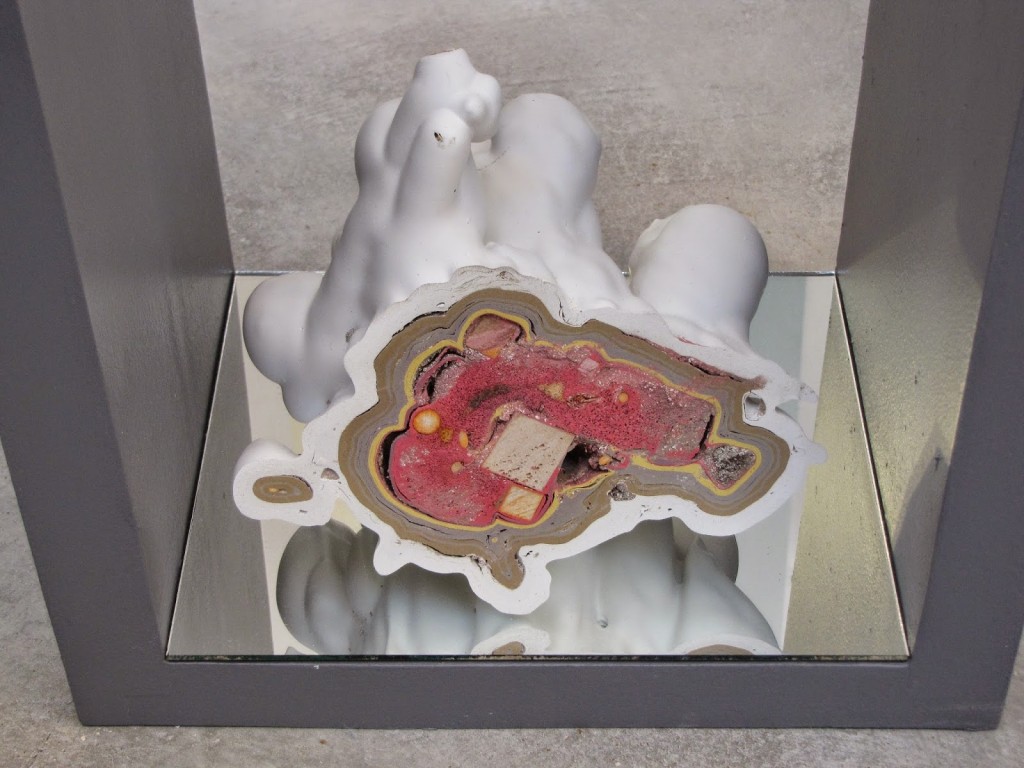

Brandon Anschultz, Suddenly Last Summer

Inspired in part by Tennessee Williams’s play, Suddenly Last Summer, Brandon Anschultz’s installation of the same name consists of multiple, semi-architectural structures supporting biomorphic objects made from layers of paint built up over studio detritus, like sponge and pieces of wood. This is smart work smartly exhibited, with Anschultz’s deceptively playful shapes and hues drawing the viewer into a world filled with darker dramatic tensions. Within each vignette, the colorful, zig-zagging scaffolding and mirrored surfaces frame the paint-objects, multiplying and restricting the visitor’s views in a way that is both generous and withholding, while the luscious tactile quality of the objects similarly taunts the onlooker who is unable—due either to physical hindrances or in deference to accepted museum behavior—to touch them. The installation thus cultivates a sensation of repressed longing that resonates with the tenor of Williams’s mediation on sexuality from the late 1950s.

With their surrealist nod to the erotic potential of abstract but suggestive objects, Brancusian play between support and sculpture, and concern with controlled but multiple viewpoints, Anschultz’s installations are clearly indebted to the history and concerns of sculpture, even as they represent a particular fascination with the physical qualities of paint. More than yet another reinvention of painting, however, his works—like those of his co-exhibitors—both celebrate and reaffirm the importance of materiality in art at a time when such affirmation is as welcome as it is necessary.

The Great Rivers Biennial opened on May 9 and will run until August 10, 2014 at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz.